Viruses are packets of genes on the run. They don't have any fancy biological equipment of their own, and must hijack the cells of living organisms in order to replicate. Some viruses go as far as integrating with our DNA to become part of us forever. Depending on your mood, you might call them intracellular parasites, mobile genetic elements, or freeloading gits.

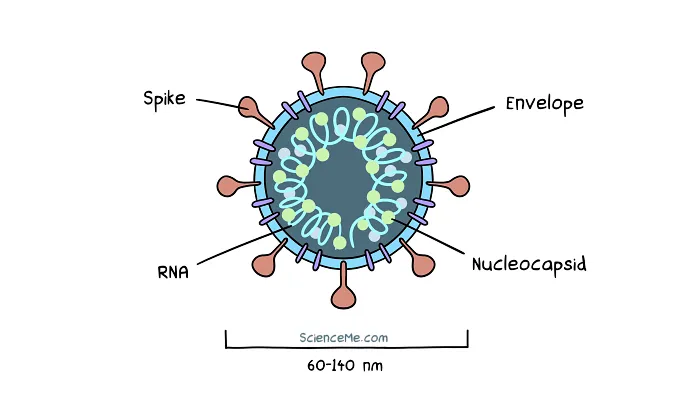

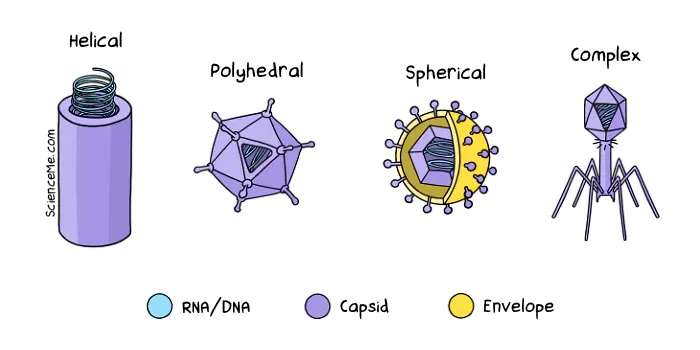

A virus is a relatively simple unit. At its core, a virus is a squiggle of nucleic acid (the storage medium of genes), protected by a protein coat called a capsid. Some viruses also have an outer membrane that's studded with "keys" like the infamous spike protein, giving them covert entry to our cells.

Cross-section of SARS-CoV-2, an enveloped virus with single stranded RNA.

Through the course of evolution, viruses have evolved to parasitise bacteria, plants, fungi, and animals. There are an awful lot of them: vertebrates alone are hosts 3.6 million virus species, while the human gut contains 140,000 species that infect our symbiotic gut bacteria.

Viruses come in four flavours: helical (eg rabies), polyhedral (eg adenovirus), spherical (eg coronavirus), and complex (eg bacteriophage).

When viruses infect our bodies, they damage our cells and trigger an immune response, creating the symptoms of infectious disease. But enough about disease. What are viruses, where do they come from, and what do they want?

Are Viruses Alive?

Traditionally, biologists said no: viruses are not alive because they lack the equipment to metabolise, grow, and self-replicate.

But viruses do possess genes. Which means they can mutate, adapt, and evolve. They also share a common genetic code with all living cells, suggesting they once branched from the universal tree of life.

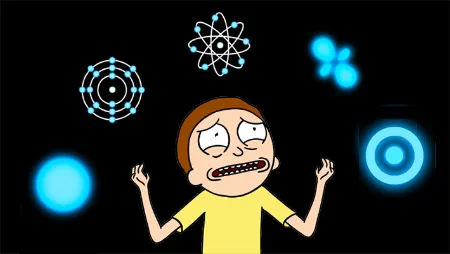

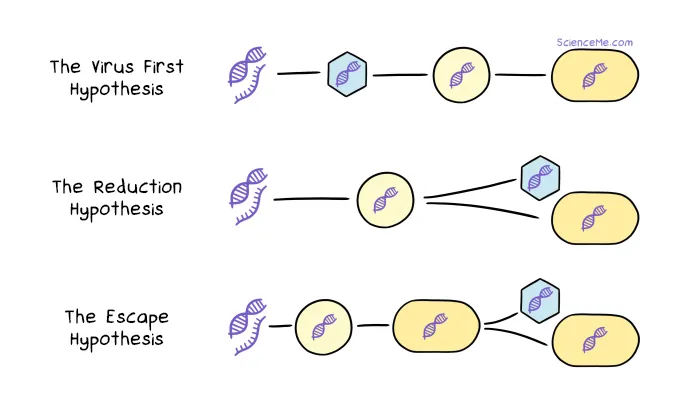

So if they're no longer alive, how did viruses evolve to be relegated to the world of the undead? Here are the three main hypotheses of viral origins:

Classical hypotheses of viral origins. (1) The Virus First Hypothesis says viruses preceded all cellular life. (2) The Reduction Hypothesis says some primitive cells spun-off into the first viruses, while others became modern cells. (3) The Escape Hypothesis says viruses are genes that evolved to survive outside modern cells.

Recent comparisons of viral and cellular proteins reveal intricate overlaps in their proteomes (protein sets). This favours the reduction hypothesis, where early parasitic cells dropped their standard equipment to become the first viruses.

Fast forward a couple billion years. Modern viruses are so streamlined as to have just 4-200 genes. This compares to 180-12,000 genes in bacteria, and around 20,000 genes in humans. (Just to mix things up a bit: water fleas have 31,000 genes.)

So the question—are viruses alive—is somewhat open. We might think of viruses in the wild as dormant, coming to life only when they hijack cells. While some simply redirect our biological machinery, others set up compartmentalised virus factories where they metabolise and reproduce with autonomy. It's life, Jim, but not as we know it.

How Viruses Integrate with Our DNA

Most viruses don't appear to insert their genes into our own DNA. But there are exceptions.

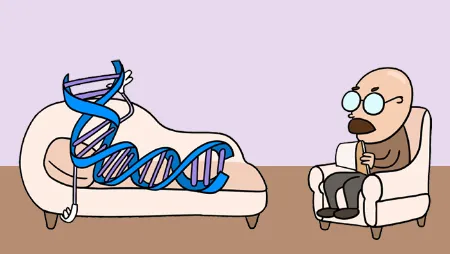

Retroviruses are hell-bent on eternal life, integrating their DNA alongside our own. Clinically, the most significant one to do so is the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) which causes AIDS.

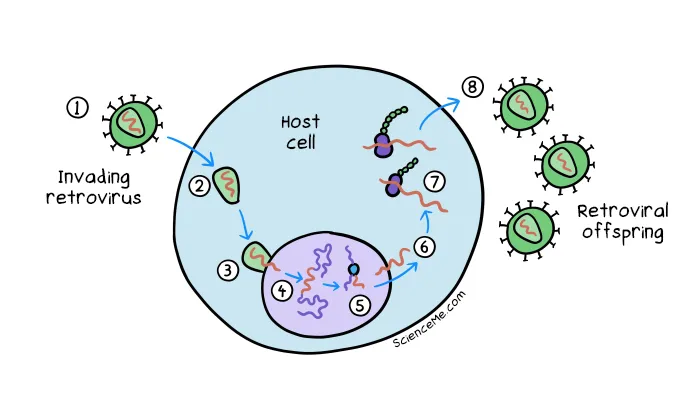

How does this happen? The HIV virus uses an enzyme called reverse transcriptase to convert its single-stranded RNA into double-stranded DNA. It then injects its DNA into a nuclear pore complex, penetrating the host cell nucleus. An enzyme called integrase catalyses the insertion of the viral DNA at target sites, giving the viral genes a forever home inside our cells.

In this purely genetic form, the virus is known as a provirus. Nestled alongside the genes of its host, proviruses are expressed to reproduce HIV for life.

The retrovirus infection cycle. (1) The retrovirus binds to a cell receptor to gain entry. (2) Reverse transcriptase converts the viral genome from RNA to DNA. (3) The capsid injects the viral DNA along with an enzyme called integrase into the nucleus. (4) Integrase catalyses the insertion of viral DNA at target sites to create a permanent store. (5) To replicate, the provirus is then transcribed back into mRNA which is (6) exported out of the nucleus. (7) The mRNA is translated into viral proteins which self-assemble and (8) exit the cell.

Typically, the HIV virus targets immune cells, which is what ultimately leads to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) if left untreated. But can HIV attack other cells too. When it infects germ cells (ie, sperm and eggs), it hitches a ride in the genome of future generations.

Today, we all have proviruses inside our DNA—or at least, the fragmented remnants of their genes. But if natural selection prunes away useless genes, why are proviral sequences still with us today?

How Viruses Shaped Our Evolution

When proviral genes land in host DNA, they can be co-opted for new purposes, ultimately driving new adaptations.

For instance, a select group of retroviral genes were put to work in mammals 130 million years ago. They bestowed our ancestors with novel proteins that supported fusion between cells, facilitating the evolution of the placenta.

This is how viruses changed the course of animal evolution: they actually handed us cool new genes.

But there is a finite window in which we can take advantage of viral genes. Over time, the unused sequences become corrupted by random mutation, degrading into strings of non-coding DNA which clutter up our genetic bank.

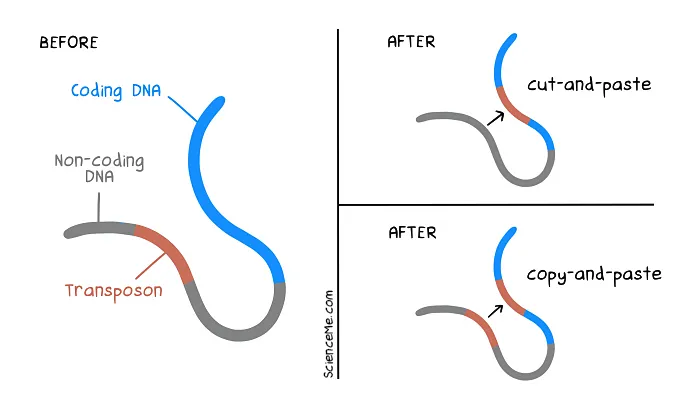

What's more, viral elements have a propensity to replicate within our genome using a copy-and-paste style mechanism. It explains their astonishing abundance today: of the 3 billion bases in human DNA, up to 1.4 billion may have viral origins.

Once written off by geneticists as junk DNA, these non-coding snippets of As, Cs, Gs, and Ts are now thought to have valuable functions. For instance, they may provide a genetic sandbox from which novel genes can emerge.

Then there's the extraordinary facility of jumping genes.

Jumping Genes

Around half of our DNA consists of transposable elements—sequences of A, C, G, and T bases that move around within our genome, earning them the moniker of "jumping genes". A large portion of these elements have proviral origins.

When jumping genes copy-and-paste themselves within our DNA, the precise landing site determines whether our DNA is altered in a positive, neutral, or negative way.

Jumping genes can interrupt the sequence of coding DNA to start, stop, and alter the expression of our genes. In evolutionary terms, this can be hugely beneficial. But as individuals, we're nature's guinea pigs.

Retroviruses have also littered our genome with extra promoter sequences, which serve as on-switches when located at the start of coding genes. We've successfully co-opted many viral promoters in our evolution.

And yet there are some genes we very much want to keep switched off under normal circumstances. This is where jumping promoters can cause problems.

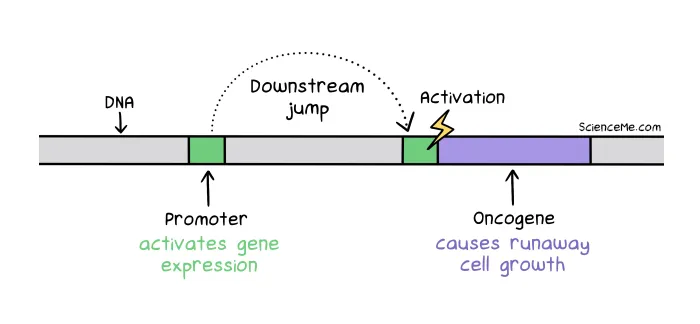

Consider that we have around 40 genes that direct cell growth and repair. When they're not required, they're inactivated. Switching them on in error can lead to runaway cell growth—aka cancer.

For this to happen, a proto-oncogene must first undergo a mutation to become an oncogene. Now it's a gun, cocked and loaded. Although we have many checks and balances to avoid it firing, jumping promoters can pull the trigger.

When a promoter jumps and lands near the start of an oncogene, it can trigger cancer.

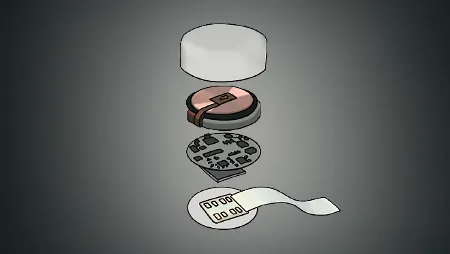

Jumping genes: a promoter sequence jumps downstream to activate transcription of an oncogene.

Research is uncovering a growing number of mechanisms by which these self-appointed gene managers can trigger diseases like ALS, MS, haemophilia, and schizophrenia. So how often do genes jump?

The most abundant jumping gene, Alu, makes up around 10% of our DNA. At 300 base pairs long, Alu has copied and pasted itself a million times since it took up residence in our genome 65 million years ago. These mobile genetic elements are so active that new Alu insertions are estimated to affect 1 in 20 births.

Is this bad? Not always. In the course of evolution, Alu sequences have been co-opted as gene regulators, helping control gene expression throughout the lifetime. Unfortunately, Alu jumps can also trigger blood and neurological disorders.

However, for the most part, Alu elements usually land in non-coding regions, which rather adds value to that so-called junk DNA.

Final Thoughts

Viruses are everywhere. In supermarkets. In labs. In bacteria. In our DNA. We even use them in medicine: viruses can be adapted to carry genetic material to our cells, whether to cure disease with gene therapy or prevent it with genetic vaccines.

Viruses have been around for billions of years and, looking at the state of our genome, will be with us for a long time to come. Good or bad, dead or alive, if there's one thing you can say about viruses... it's that they're spectacularly successful at what we're all ultimately programmed to do: replicate our genes.

Written and illustrated by Becky Casale. If you like this article, please share it with your friends. If you don't like it, why not torment your enemies by sharing it with them? While you're at it, subscribe to my email list and I'll send more science articles to your future self.