Are we just fleshy automata? Biologically speaking, we breathe, grow, and reproduce on autopilot. So what does science have to say about consciousness and free will?

It was once thought that life on Earth could not be reduced to a nuts-and-bolts explanation by science. Yet that's exactly what happened—scientists ditched the notion of a mystery life force when it became clear that our existence arises from biological, physical, and chemical origins.

Now, the same revolution is occurring with the science of consciousness. While most people—theists, atheists, and agnostics alike—still believe in an ethereal mind or spirit, neuroscientists are gathering increasing amounts of evidence for consciousness as a physical property of the brain.

"Perhaps consciousness arises when the brain's simulation of the world becomes so complex that it must include a model of itself." - Richard Dawkins, The Selfish Gene

This self awareness is what creates the confusion. It makes it harder to intuit the conclusion of empirical evidence: that our brains run on autopilot.

The Frontal Cortex Changes Everything

The most basic animal life forms, like sponges and sea anemones, have no consciousness at all because they have no brains. Their existence follows rules of cause and effect at the molecular level.

But what about more complex animals with the capacity for conscious thought? Does consciousness give rise to free will—and if so, how?

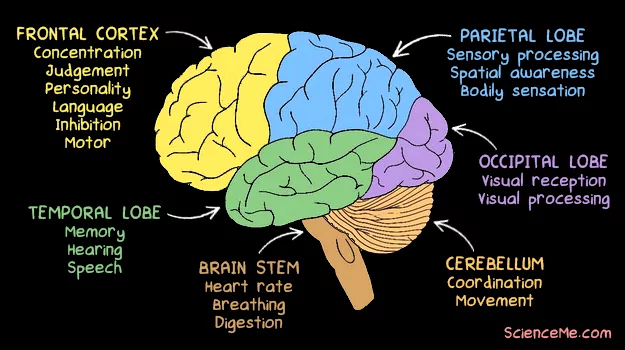

Our brains execute many automatic functions which we don't control, like digestion, sensation, and auditory processing. However, there are also functions which we feel we can direct, like concentration, language, and problem solving. These take place in the frontal cortex.

This is the most recently evolved part of the brain. It allows us to selectively focus our awareness and attention, which generates the perception of freedom and independence from these automatic processes.

The human brain is split into six parts (figuratively speaking): the frontal cortex, parietal lobe, occipital lobe, temporal lobe, cerebellum, and brain stem.

Humans have evolved the biggest frontal cortex, giving us the broadest range of higher functioning. This not only suggests animals with a larger cortex have a greater capacity for conscious awareness, but that consciousness emerged gradually, following a continuum of animal evolution.

In other words, there was no single point at which our animal ancestors evolved consciousness, the same way night doesn't turn to day in an instant. It was a gradual process of dawning.

The possibility of free will must lie within consciousness. Does consciousness outrank biology, allowing us to control elements of our experience ahead of our genetically-driven necessity for survival? Or is everything we do at a conscious level driven by biological need, and later analysed and justified by conscious thoughts?

To find more clues, let's examine the nature of consciousness itself.

What is Consciousness?

Neuroscientists view consciousness as a biological phenomenon, incited by neurobiological processes. Uniquely in biology, it's subjective in nature. But that doesn't mean we can't probe it in an objective manner.

Consciousness can be broken down into two types:

-

Automatic Arousal. This arises in the brain stem. Sleep-wake cycles, heartrate, and breathing are examples of passive, automatic systems.

-

Awareness. This arises in the frontal cortex. Memory retrieval, problem solving, and decision making are examples of active, intentional systems.

In deep sleep, our awareness is shut down. But during anaesthesia, both forms of consciousness shut down. Propofol, a common general anaesthetic, was recently discovered to disrupt presynaptic mechanisms, stalling chatter between neurons across the entire brain.

This is why waking from anaesthesia feels so different from waking from sleep. In many respects, you are "dead to the world" under anaesthesia. You lose all sense of time. Loud noises don't wake you. Both automatic arousal and conscious awareness cease to be, tying their dependence to a functional physical brain.

Where is Consciousness in The Brain?

Neuroscientists have examined the specific brain processes associated with consciousness. For example, this observational study of consciousness used fMRI to scan the brains of 12 healthy volunteers.

"When we lose consciousness, the communication among areas of the brain becomes extremely inefficient, as if suddenly each area of the brain became very distant from every other, making it difficult for information to travel from one place to another." - Monti et al., UCLA

Consciousness doesn't reside in a single area in the brain, but rather, is how the brain "talks" to itself. If your experiences, memories, and emotions are towns and cities spread across a country, consciousness is the interconnected network of roads, highways, and spaghetti junctions that facilitate movement between them.

This is the essence of Passive Frame Theory, which says that consciousness is an interpretive process that connects different pockets of brain activity. However, as an interpreter, consciousness merely passes on information. It doesn't add new information of its own.

The latest science suggests consciousness is merely a middle-man of automatic thought processes. It's no more separate from the physical brain than the flow of water is separate from a river.

Do We Have Free Will?

Our subjective experience of consciousness makes us feel as if we have free will—as if we have degrees of mental independence from our biological machinery. Free will makes us feel as if we're eligible to make choices and take ownership of our lives.

Buddhist philosophers have countered this hypothesis for millennia. They say there is no self, and free will is an illusion. Now scientific evidence is mounting to support the idea that free will is indeed a trick of the mind.

In 1999, Wegner and Wheatley proposed that our sense of free will is a rapid-firing afterthought that justifies our decisions. This justification has no causal role in our decision making.

What will you eat for your next meal? Is it a free choice, or is it a deterministic decision-making process based on existing factors? Your next meal will depend on the availability of food, cultural influences, nutritional requirements, biological cravings, and taste preferences which arise from your genetically and experientially programmed taste buds. The non-empirical element of free will is extinguished by these empirical influences.

Let's examine a more meaningful choice, like selecting a life partner. There are countless factors outside of your control that determine who you settle down with. Consider the sexuality you're born with, the availability of mates, society and culture, physical attractiveness, personality type, past experiences, and pheromones.

Philosophically speaking, no-one chooses to fall in love. They just do. Biological chemistry has a lot to answer for—and this is something we can measure directly. We can't say the same for free will.

As you examine more and more parts of your life where free will seems to exert an influence, it becomes harder to find a place for it. From animalistic urges, like sex and reproduction, to intellectual pursuits, like education and career choices, we are fundamentally driven to survive, to seek pleasure, and to avoid pain.

What About Creativity?

"Aha!" you exclaim. "But there's no biological drive for creativity... is there?"

Evolutionary biologists have a rather unique way of thinking about life. They see all physical and psychological mechanisms in terms of their survival value. These evolutionary explanations hold true right down to abstract behaviours like creativity, dreaming, and altruism.

Creativity is a trait our ancestors evolved to overcome barriers to their survival. It helped hunter-gatherers develop complex language so they could forward-plan, strategise, and coordinate. It helped them invent tools, build shelters, and treat wounds. Creativity arose directly as a result of problem solving.

Hundreds of thousands of years later, our innate desire for creativity serves us well in advancing our technological, scientific, and cultural prowess. Personal creativity improves the survival of entire societies, which feeds back to our individual survival. There is a biological mechanism for creativity, embedded in our DNA.

But isn't creativity a product of free will thought processes? Where does creativity come from if not spontaneous imaginative thinking?

Sometimes creativity is a conscious thought process. We use our imagination—generating simulated sensory data—to explore ideas, make connections, and reach new conclusions. But many artists and inventors credit true inspiration to the unconscious mind:

"When you have a real important problem, you don't let anything else get the center of your attention—you keep your thoughts on the problem. Keep your subconscious starved so it has to work on your problem, so you can sleep peacefully and get the answer in the morning, free." - Richard Hamming

If creativity arises from unconscious processes, then this doesn't point us to a source of conscious free will either.

Is The Brain Deterministic?

Classical physics has always found the universe to be deterministic: a theoretically predictable unfolding of events in a clockwork universe. Does this mean our brains are deterministic too? If so, this would be the nail in the coffin for free will, which by definition is a spontaneous act without the constraint of necessity of fate. If you could predict someone's free will, then it wouldn't be free at all, but rather an accumulation of external and internal pressures.

This is where the problem deepens. Classical physics doesn't give us the whole picture, and the emerging sister science of quantum physics is inconclusive. In fact, quantum uncertainty conflicts with classical physics, showing that sometimes particles shun determinism altogether. Instead, they behave probabilistically, taking the form of waves of potential that aren't subject to pre-determined outcomes.

This is what led us to tentative hypotheses like the Copenhagen Interpretation and the Many-Worlds Interpretation. For a fuller explanation of these ideas see What is Schrodinger's Cat?

It appears the universe isn't entirely deterministic. And since the brain is made up of both classical and quantum particles, we can't claim the brain is 100% deterministic either.

Free Will Isn't Testable

To date, there's no evidence that free will exists. There's no hard evidence that it doesn't exist either—only an absence of evidence. So where does this leave us?

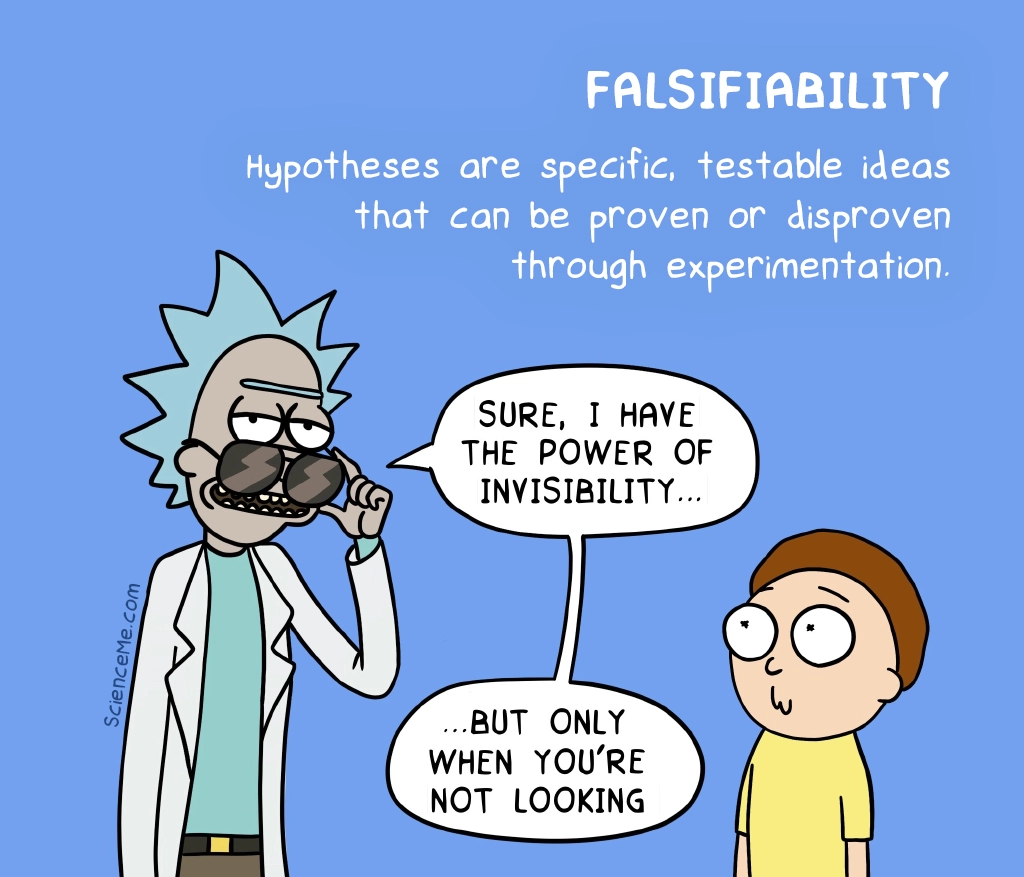

The claim of free will currently lands on the periphery of scientific analysis. To be able to test the hypothesis that it exists, the mechanism must be falsifiable, that is, framed in such a way that we can perform experiments to verify or disprove it. Since the only evidence we have for free will is subjective and anecdotal, we don't know where to point our empirical lens.

The problem with free will is that it's not falsifiable.

Science therefore says we should take a sceptical stance towards the claim of free will. It may exist beyond the bounds of observation, but there's no good reason to simply assume that it does.

This directs us away from hard science and into the realm of philosophy. Philosophy is the oldest science of all. Devoid of scientific instruments and experimental data, it relies on critical thinking and logic to tackle the toughest questions. Naturally, philosophy is inconclusive, but it does pave a way to greater understanding, to a place where we can one day ask scientifically falsifiable questions.

So what does philosophy say about free will? Quite a lot, actually. The nature and implications of free will have been explored by many key figures in Western philosophy, including Plato, Aristotle, Augustine, Aquinas, Descartes, and Kant. The thread has become more tangled with related concerns like metaphysics, ethics, causation, time, reason, and motivation. This is not an easy question to answer.

So let's finish with just one aspect of this question. The one that a sceptical philosopher might ask.

What Are The Implications of No Free Will?

Sam Harris is a neuroscientist and a philosopher who tackles the subject in his book Free Will. He explains that the concept of free will touches almost everything that we value in society. Law, politics, religion, public policy, relationships, and morality are all geared to the notion that everyone is a personally accountable source of their own thoughts and actions.

If there's no free will, the morality of society becomes illogical. How can we punish a murderer who never chose to kill? How can we be angry at a cheating spouse for fulfilling their biological impulses?

Yet we still need justice. To identify and isolate the serial killer for the sake of our community. Rather than punish, however, perhaps we should seek to treat and rehabilitate. We can leave the deceitful spouse, but rather than be consumed by hate, we can focus on finding a partner with monogamous values.

To paraphrase Harris, you don't hate a hurricane. But you can still take measures to protect yourself from it. We can do the same with toxic behaviours, all the while empathising with the people suffering from them, who are ultimately ruining their own lives too.

This could be liberating. As it stands, our belief in free will constrains us to living in an illusory cage, shaped by the stories we tell ourselves to make sense of reality. To step outside of this cage would mean accepting that, as far as the evidence tells us, we are biological machines. Ones who create unfounded narratives to feed our psychological need for control.

Written and illustrated by Becky Casale. If you like this article, please share it with your friends. If you don't like it, why not torment your enemies by sharing it with them? While you're at it, subscribe to my email list and I'll send more science articles to your future self.