Jellyfish sex is really weird. Although to be fair, they are ancient animals who mastered sexual reproduction hundreds of millions of years before us. Frankly, we're the ones odd-balling it with our penises and vaginas and miserable, painful childbirth.

How do jellies have sex? Not like that.

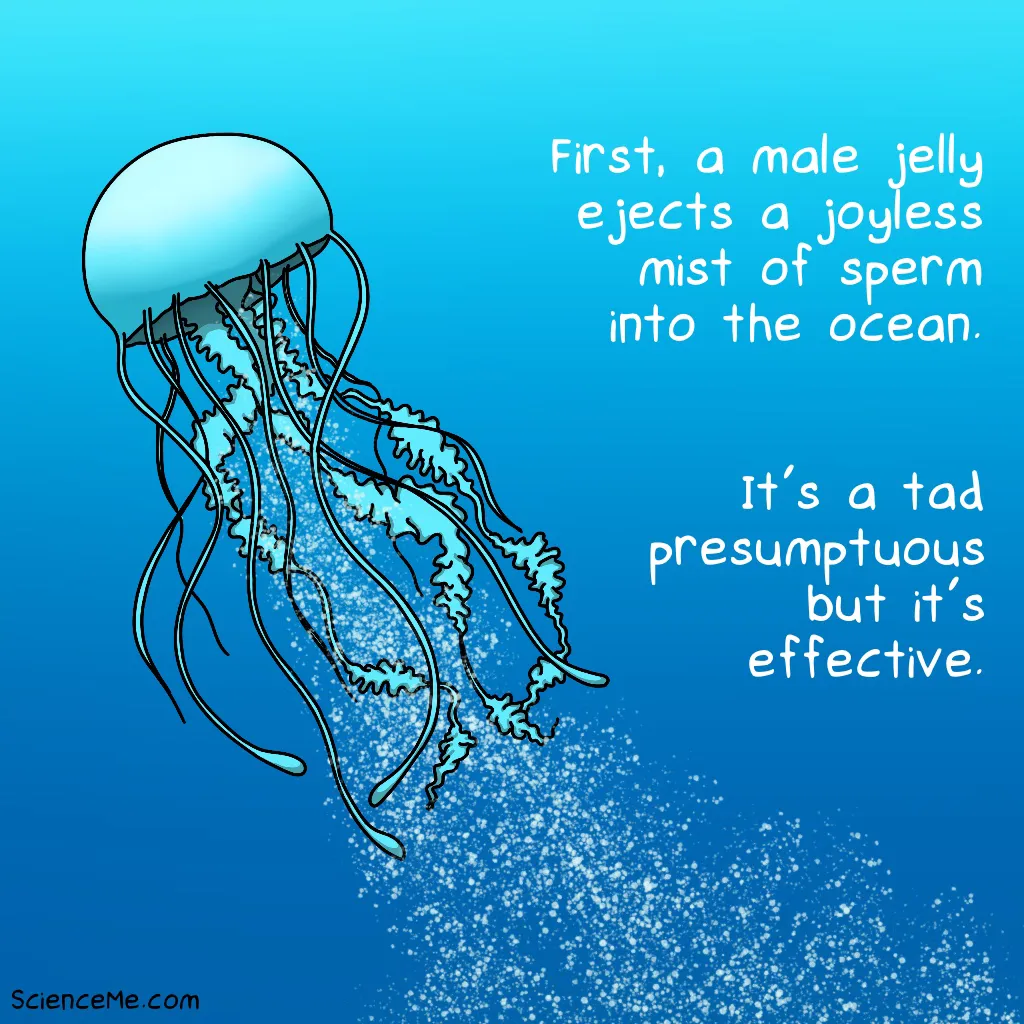

The male's role in procreation begins and ends with a spectacularly presumptuous sperm dump.

Do jellyfish orgasm? You tell me.

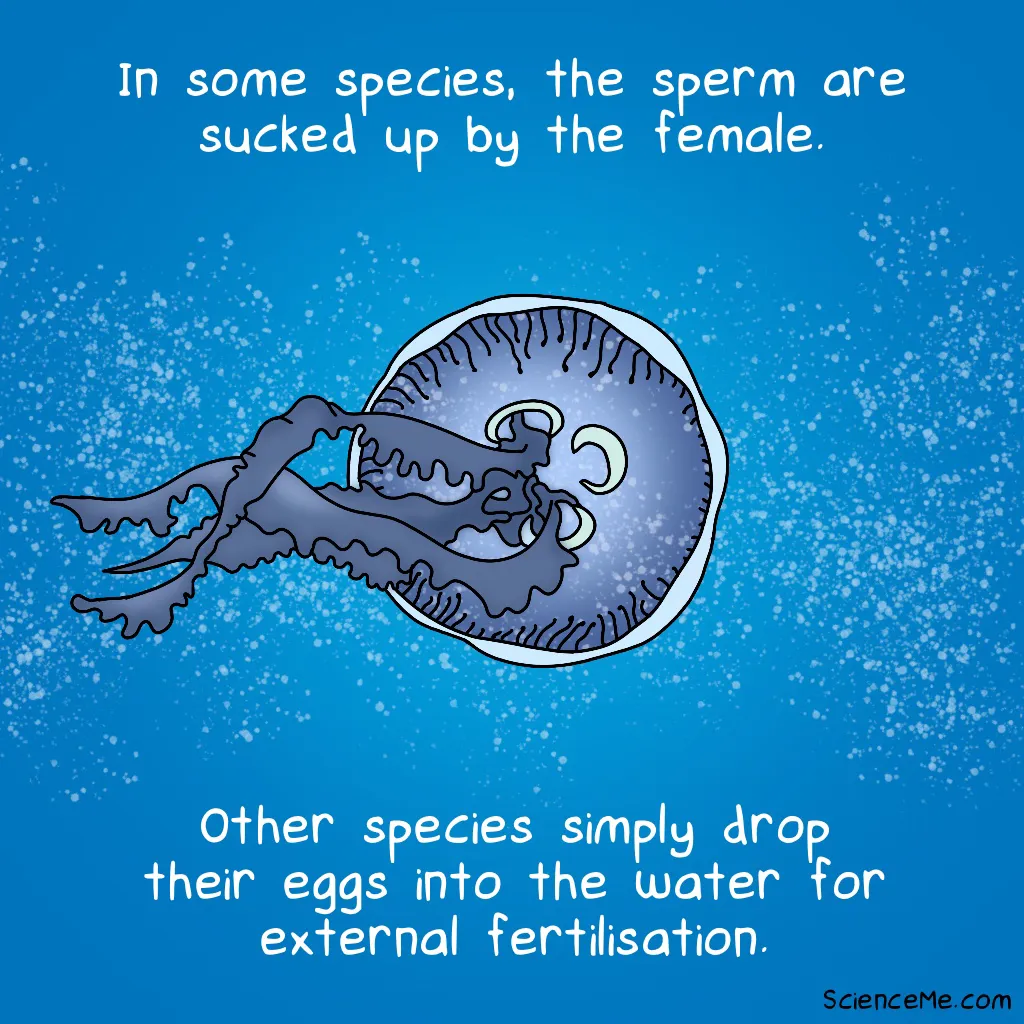

Ocean currents disperse the sperm until it's sucked up by a female jellyfish. "Sucked up? But how?" You ask, wide-eyed and captivated.

The sperm wafts into an opening in the female jelly—an opening that functions as a vagina, a mouth, an anus, and any other specialised orifice you care to imagine.

Jellyfish are simple animals and evolution didn't bestow them with complex internal systems. The body is essentially three layers: an inside (the gastrodermis), a middle layer (or mesoglea, which functions as a hydrostatic skeleton), and an outside (or epidermis, just one cell thick).

Jellyfish fertilisation can be internal or external. Remember this when you're swimming in the ocean.

Jellyfish Fertilisation

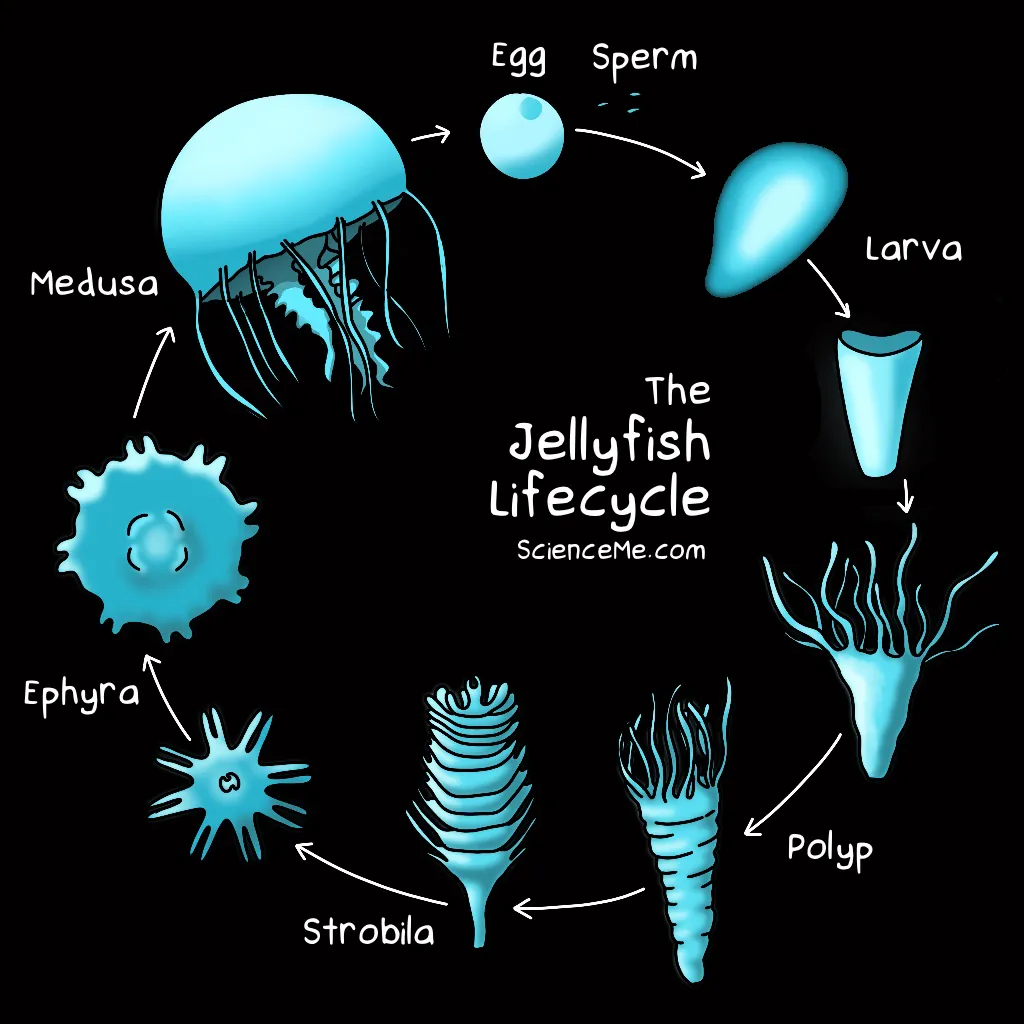

Whether inside a female jelly or out in the ocean, the sperm fertilise the eggs. This is the crux of sexual reproduction, where the DNA of two parent individuals mingles to produce genetically original offspring.

The genital dance we associate with sex on land is completely unnecessary in the ocean, where the water provides a top notch medium for eggs and sperm to meet.

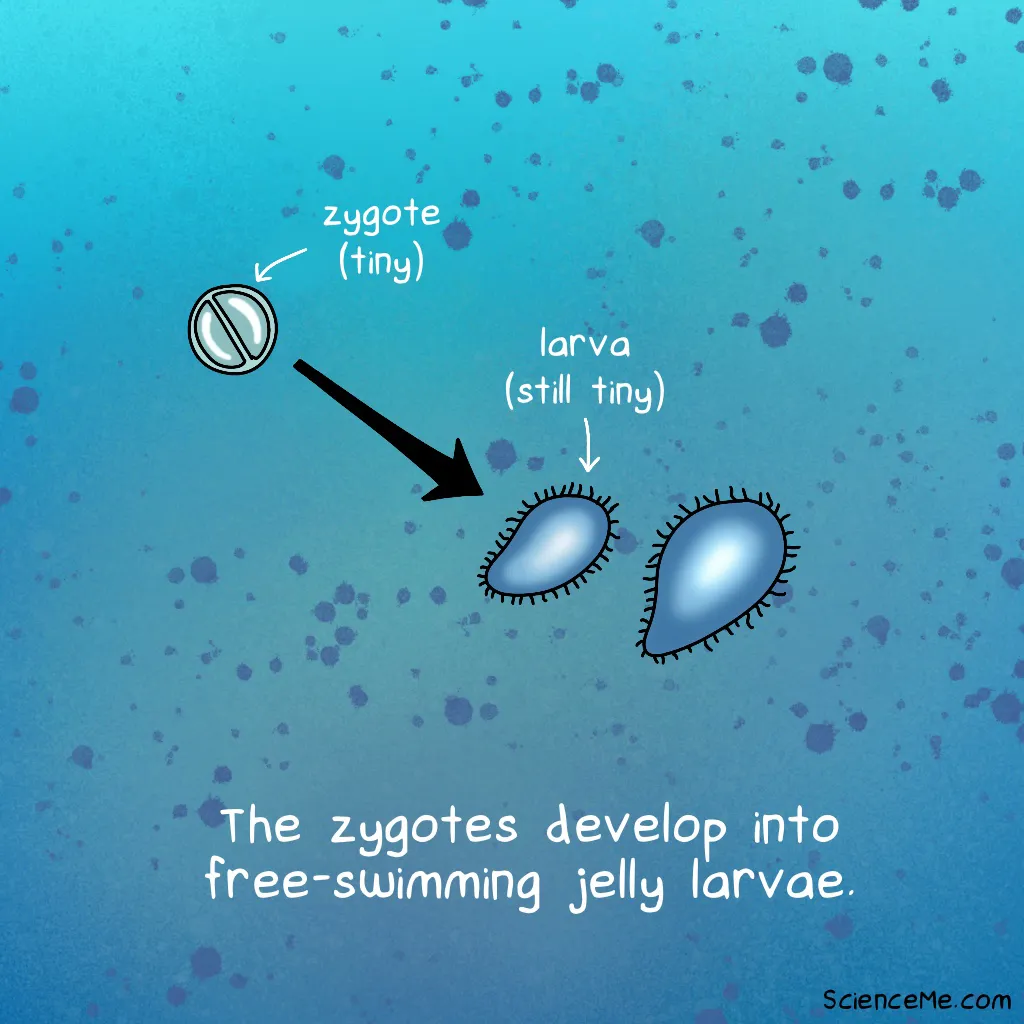

Even when fertilisation takes place inside the female jelly, her maternal role is ludicrously brief. She hosts the fertilised zygotes for a few days until they hatch into free-swimming larvae—and swim off into the ocean forever.

Jellyfish larvae look like jellyfish in the same way that human embryos look like people, which is to say: not a lot.

This seems like a sensible time for the larvae to develop into adult jellies and complete the lifecycle of the jellyfish. But that would make this article shorter than the average jellyfish penis (which we now know does not exist) and, frankly, equally disppointing. Luckily for all, jellyfish sex gets a lot more convoluted.

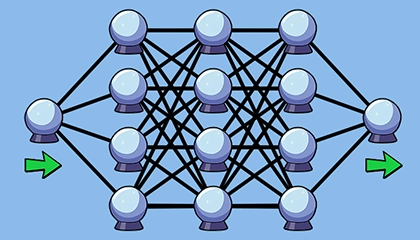

How to Clone a Jellyfish

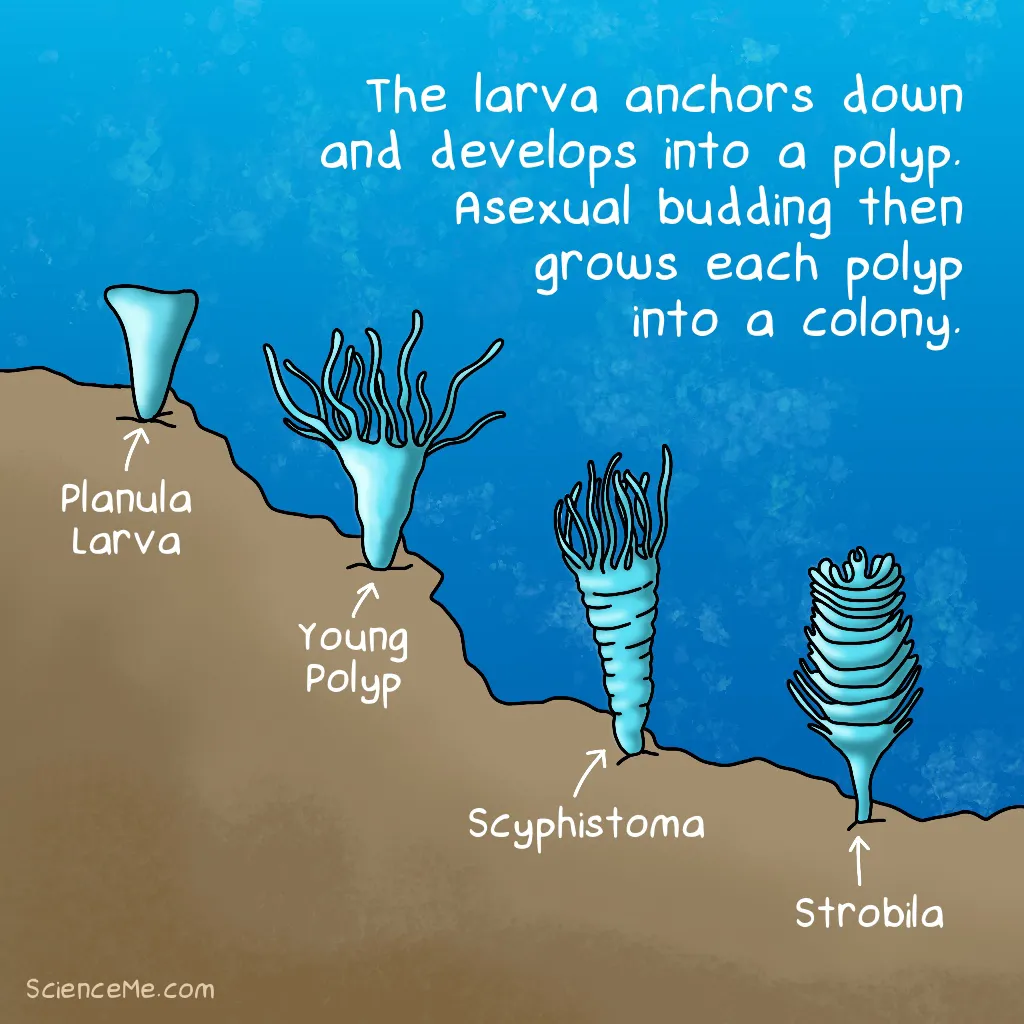

Yes, you read that right—it's cloning time. After brief period of furiously beating their cilia against the ocean currents, the larvae settle down on the sea bed or any other convenient substrate: rocks, shells, shipwrecks, car tyres, dentures, pool tables—you name it. And this occurs in all coastal waters, from the Arctic to tropical seas.

The larvae now develop into young polyps: stalk-like structures that look rather more like plants than actual animals.

This is where jellies more closely resemble their sister class, the humble sea anemone, in another wink to evolution by natural selection. In time, the sessile (immobile) jelly polyps develop into weird layered organisms called scyphistomae, identified by tendril-like tentacles emerging around the upward-facing arse-mouth.

Each larva develops into a polyp with weird intentions.

You might think that because we can sort-of see a jellyfish emerging here, the lifecycle is almost complete. Don't think that! Because not only will they drop their apparent tentacles, but they'll also go through a round of asexual reproduction, also known as reproduction without sex.

The jelly now matures into a strobila, which means it's juiced up and ready to strobilate. Sounds saucy? It isn't! Remember, jellyfish sex is not sexy. Not at all.

The polyp divides in half to produce a genetically identical twin. Then each twin divides again. And again. Soon, an entire colony of jellyfish clones emerge, all from a single original larva.

This type of asexual reproduction is called budding. Since only one parent is involved, there's no genetic variation produced, except in rare circumstances where meaningful mistakes are made in DNA replication.

Why do this? As with everything in evolution, this part of the jellyfish lifecycle occurred randomly and then stuck around because it conveyed a survival advantage. Presumably, the main advantage of strobilation is that it produces many more jelly babies, which multiplies the chances that this particular combination of DNA will be passed on to a new generation.

Next, the colony now undergoes polymorphism: where different clones develop different structures to fulfil specialised roles. For instance, some parts of the colony capture prey, some specialise in digestion, some do more cloning, and some defend the colony with stingers.

The colony—which is still only a teeny tiny polyp—covers every base for survival. It functions extraordinarily well despite being a small, primitive, sessile animal with multiple personality disorder.

How to Become a True Jelly

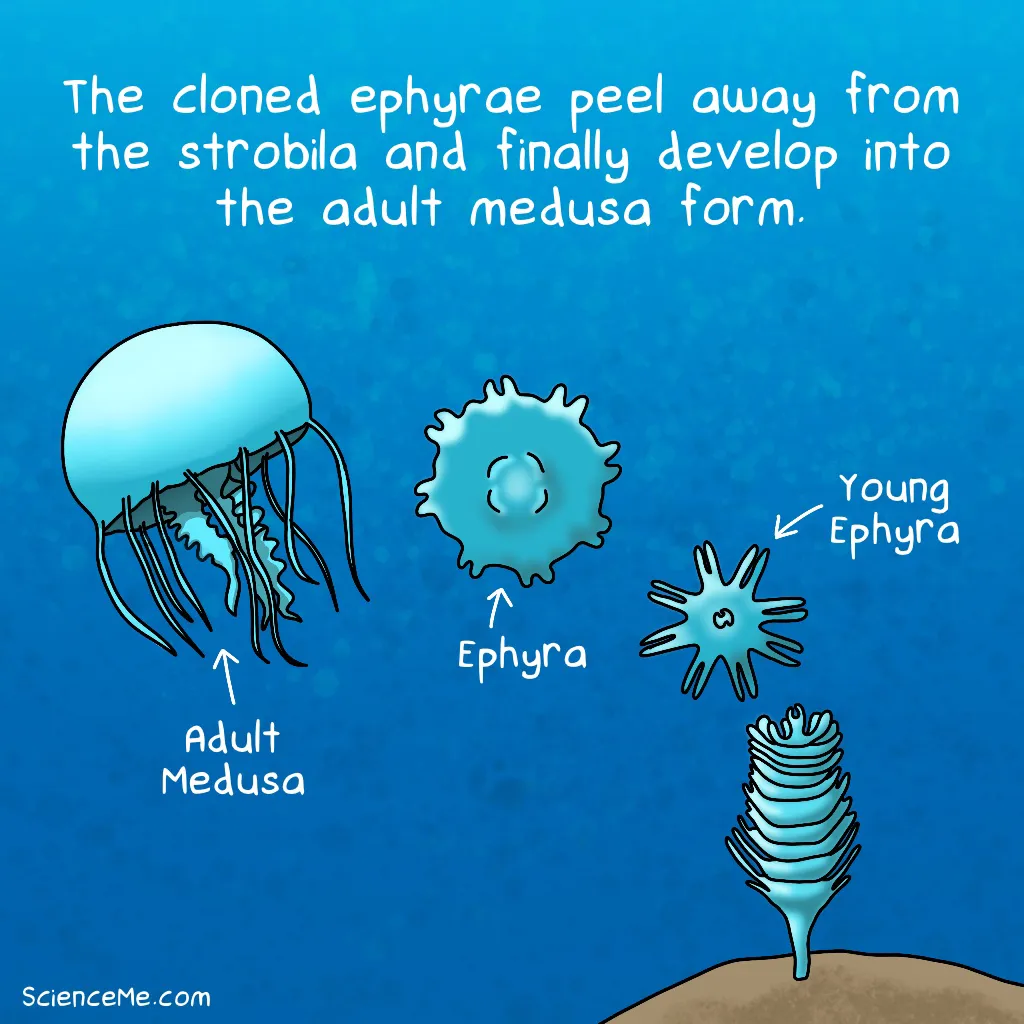

Finally, the uppermost clone peels away from the strobilated polyp colony and floats free. This jeuvenile jellyfish is called an ephyra.

Each ephyra peels away from the strobila and finally develops into the classic medusa form.

Having jumped through all these developmental hoops, it's baffling to know that the lifecycle of jellyfish is short. Set free into the ocean, the little squirts have just a few months to mature and reproduce before they die. Will they make it? Five hundred million years of jellyfish evolution says yes.

When they leave the colony, the ephyrae are tiny—about the size of a freckle. But they get bigger, developing into the classic jellyfish form known as medusae. Just how big do jellyfish get? While species like the Irukandji max out at 2 centimetres (0.8 inches), the largest known jellyfish species, the Lion's mane jellyfish, can reach 2.5 metres (8.2 feet) across with tentacles that extend 36.5 metres (120 feet) long. That's longer than the blue whale which is the largest mammal on Earth.

Jellyfish Sex Round-Up

The jellyfish lifecycle is a wild ride and, strictly speaking, this is only one version of events. Different jelly species undergo equally strange variations of the process above. Depending on how much you enjoyed this article, you'll be overjoyed or disappointed to learn that comb jellies have a much simpler lifecycle altogether. They're hermaphrodites—possessing both the sperm and eggs to self-fertilise if needed—and the larvae grow directly into adult comb jellies.

What's truly amazing to me is the jellyfish lifecycle emerged through random genetic mutation, to be pruned by nature's selection. Each time the ocean created new pressures on these otherwise simple animals, the mutants among them provided novel and more complex solutions to parent a new generation of ocean-savvy oddballs. And this is what we end up with. A bizarre, twisty rollercoaster ride of submarine jellyfish sex.

The jellyfish lifecycle.

Written and illustrated by Becky Casale. If you like this article, please share it with your friends. If you don't like it, why not torment your enemies by sharing it with them? While you're at it, subscribe to my email list and I'll send more science articles to your future self.