There are a lot of terrible diseases out there. Elephant man disease, prion disease, dying-of-old-age-at-eleven disease. But if you want the crème-de-la-crème of human misery, you can't do better than depression.

What is Depression?

Professor Robert Sapolsky, whose lecture on the biology of depression is the foundation of this article, says depression is hands-down the worst disease you can get. And it's depressingly common: 15% of us will experience major depressive disorder (MDD) in our lives, no matter where we live in the world.

Many people don't realise depression is an illness. Consider the different levels at which we refer to "depression" in everyday language versus what we're actually talking about when we say clinical or major depression.

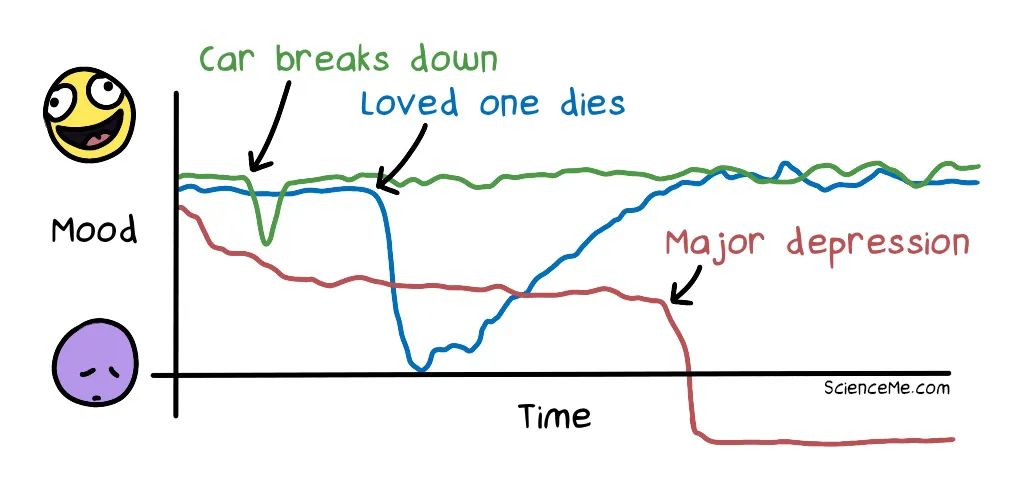

Your car breaks down and you miss out on an evening with friends that you had been looking forward to all week. "Oh my god, tonight was so depressing!" You say. This is deflation or sadness, but not depression.

Your girlfriend breaks up with you after a five-month relationship and you feel heartbroken and awful. The intense feelings lasts for days or weeks, but time is a great healer and you soon feel normal again. This is reactive depression.

Your life has become chronically stressful—or the complete opposite, chronically empty and meaningless. Everyday life provides so few positive feedback loops that you become highly anxious or altogether flat, making you feel hopeless. This is major depressive disorder.

While major depression is often triggered by external life stress, it's our internal biology and psychology that drives the permanent stress response, leading us into a state of chronic hopelessness.

"Depression is a biochemical disorder with a genetic component and early experiential influences which means you can't enjoy sunsets anymore. - Robert Sapolsky

Compare depression to another horrible and life-ruining disease like cancer. After facing their own mortality, cancer survivors often say things like "if not for the cancer, I would never have reconnected with my sibling". They're still able to see the silver lining through the adversity.

This doesn't happen with major depressive disorder. In its grip, you can be sharing a beautiful sunny day with your loved ones, but depression steals any possibility of enjoyment. Whatever the experience, the overwhelming reaction is fear, anxiety, hopelessness, or numbing ambivalence.

Depression is also a lingering disease that threatens relapse, so even after you've escaped the depths of this hellhole, you never feel completely free.

The Symptoms of Depression

Take a quick scroll through the most common signs of depression.

Anhedonia. The inability to feel pleasure. It's a hallmark of depression and is ultimately what makes it the worst disease imaginable. What's the point of living if you can never feel happy?

Guilt and rumination. Depressed people suffer guilt to a delusional extent. We might obsess about something we did to someone two decades ago, and which may be unfixable or redundant because that person has long since moved on with their life. We may also generate delusional thoughts about the present and spent vast amounts of time ruminating on real or perceived problems.

Insomnia. In reactive depression, we may lay awake at night, our minds buzzing with unresolved thoughts. In contrast, major depression causes different sleep disturbances, such as waking up at 3am and being able to can't get back to sleep no matter how exhausted we feel. Brain scans reveal that sleep phases are completely disordered, making this one of the most common depression symptoms.

Loss of Appetite. Reactive depression triggers comfort eating, which is logical because sugars and carbohydrates decrease the release of stress hormones. However, major depression has the opposite effect: anhedonia means there's no pleasure or comfort in food. The scorned romcom starlet who sobs into a jumbo tub of octuple chocolate ice cream does not have major depression.

Hopelessness. Sapolsky gives us an example of a 50-year-old engineer who has a heart attack. He's admitted to hospital and the doctors say he has to change his lifestyle but he's going to make a good recovery. However, instead of writing a bucket list, the psychological trauma of the experience leaves the man with major depressive disorder. The world loses its colour and he feels utterly hopeless about the future.

Delusion. While doctors insist the man can recover, he creates cynical and even delusional counterarguments. What if the medication doesn't work? What if I can't get into an exercise regime? What if I was supposed to die that day and now Death is coming after me? Depression and anxiety compels us to prove the future is bleak, because it aligns with the way our neurochemistry makes us feel.

Self-harm and Suicide. To people suffering from deep psychological pain, self-injury and self-mutilation can provide temporary relief by way of distraction. People suicide not because they want to die, but because they don't want to feel pain anymore and they've run out of coping mechanisms. Along with car accidents, suicide is the leading cause of death in teenagers and young adults, who are the most vulnerable people in terms of undiagnosed and untreated depression.

Psychomotor retardation. Everything is exhausting when your motivation for living is at absolute zero. The idea of a single chore like doing the washing is a long road to nowhere; it's so much effort for zero neurochemical reward. This is not the stage when you worry about suicide. Someone who is catatonic or too exhausted to get out of bed isn't going to shred the sheets to make a noose. It's when they come out of psychomotor retardation they're at highest risk of suicide.

We all feel sad and withdrawn at times, and the symptoms of depression may even be relatable to some extent, even if we've never been clinically depressed. Fortunately, most of us can get a good night's sleep, have a long talk with a friend, or make some life changes. And things start to feel better. The least-informed people tend to assume a depressed person must be able to do the same.

Sapolsky argues that depression is fundamentally a biological condition, like a stroke or a heart attack. There's no quick return to health. It's a gradual recovery that often involves medication, psychotherapy, and physical and behavioural changes.

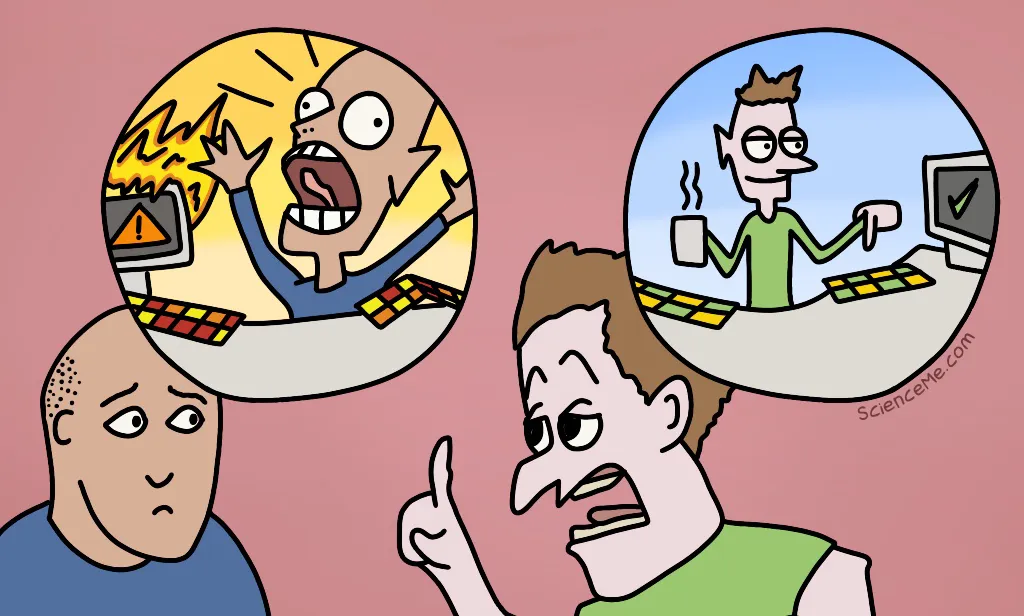

Imagine your partner is mired by psychomotor retardation and unable to get out of bed. It's tempting to think of him as lazy. But if you could look under the hood, you'd see his sympathetic nervous system is wildly overactive. He's blasting through stress hormones in an epic internal battle. His stress responses, like the spike of anger we feel when someone cuts us off in traffic, are sustained and constant, which is liable to make him feel angry, anxious, fearful, exhausted, pessimistic, or stressed out at any given moment.

Major depressive disorder often has a rhythm. You may experience two months of extreme symptoms and then go through a recovery period with mild or no signs of depression for 18 months. Then, seemingly out of nowhere, there comes another two months of intense depression symptoms.

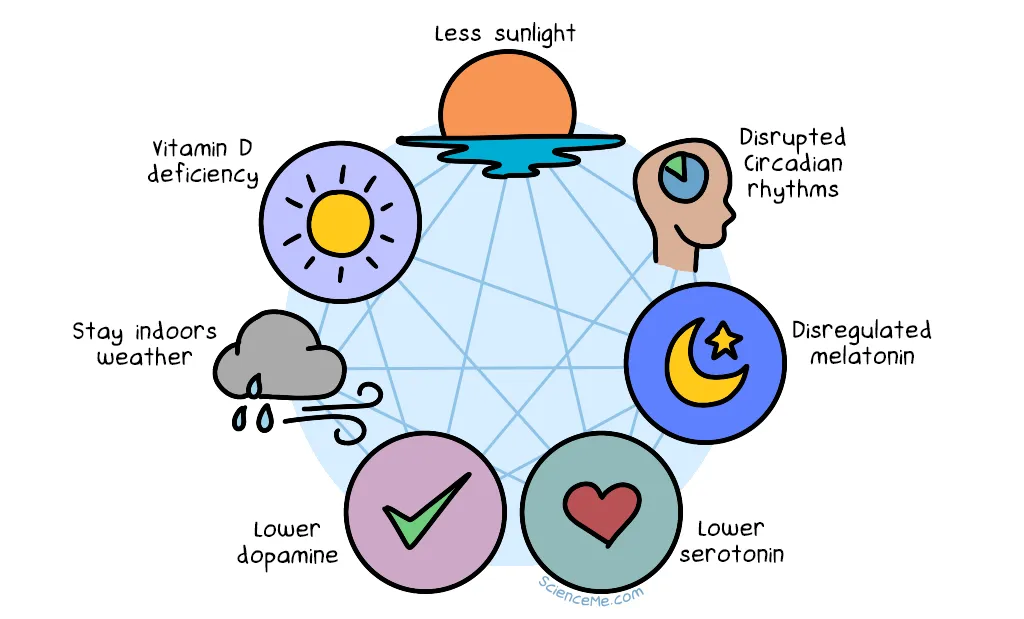

The physical and neurochemical causes of Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD).

Neurotransmitters and Antidepressants

When you talk to another human, your lungs push air through your larynx to create soundwaves, which you shape into words with your mouth. The sound is then transduced by their cochlea and interpreted by their brain.

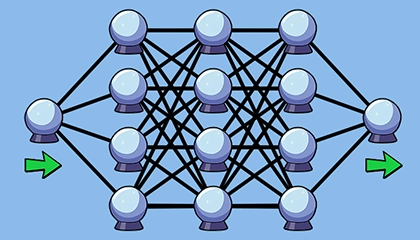

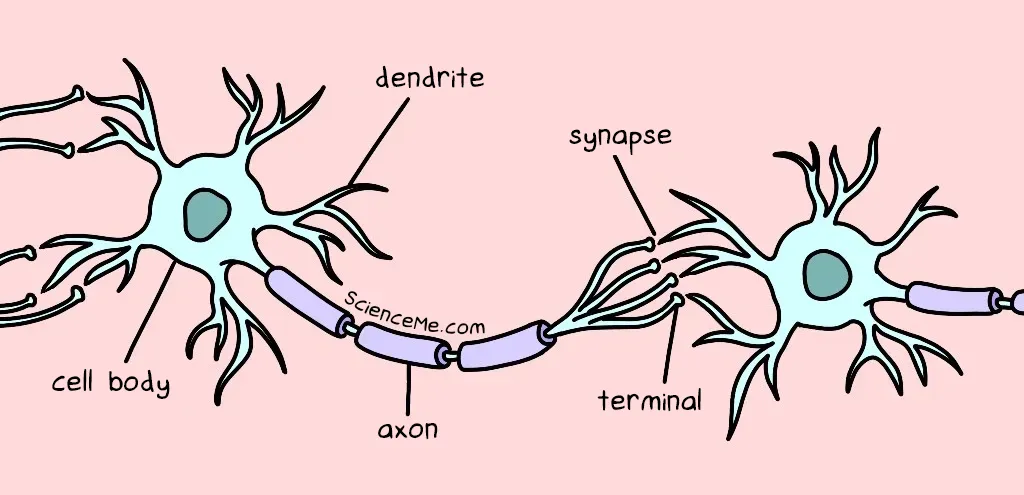

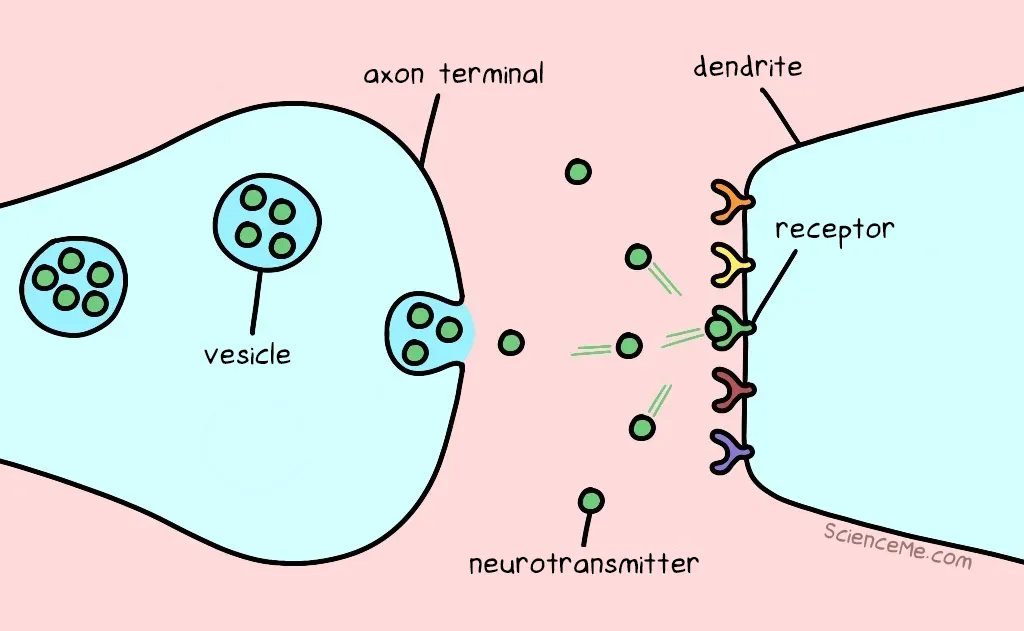

When a neuron talks to another neuron, an electrical signal prompts the release of chemical messengers called neurotransmitters, which travel into the space between neurons called the synaptic gap.

A friendly (one-way) chat between neurons.

The neurotransmitter momentarily binds to its corresponding receptor on the receiving neuron. This activates another electrical signal which travels down the axon of the receiver neuron. The message is carried forward.

Neurotransmitters being released by one neuron and hitting a receptor in another.

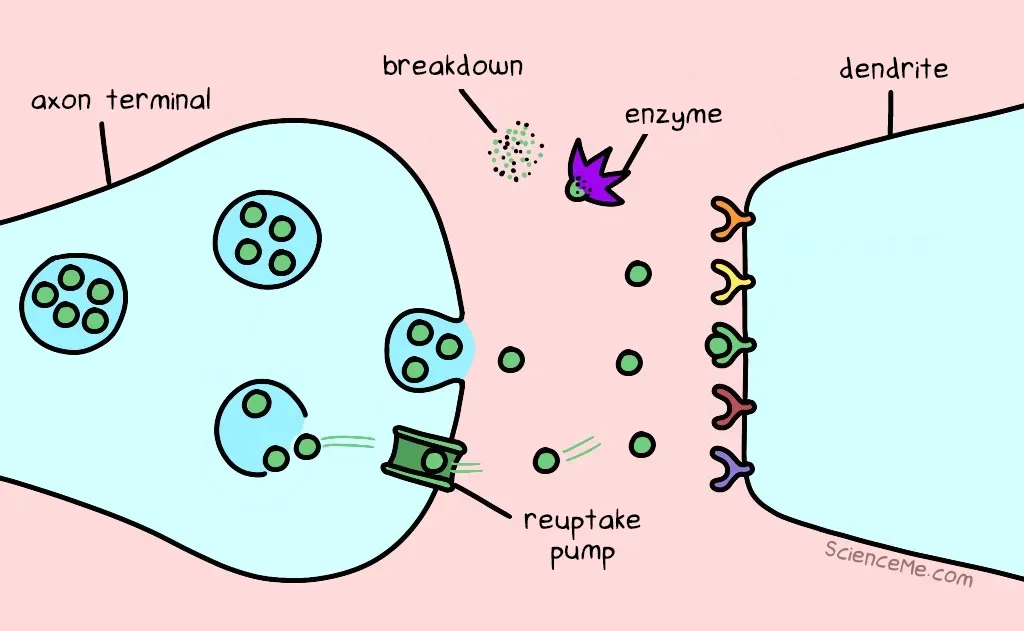

Once they've sent a message, neurotransmitters have no place in the synapse. So they're either recycled back into the transmitting neuron (known as reuptake) or broken down by enzymes and flushed out of the body in your pee.

The reuptake and breakdown of used neurotransmitters.

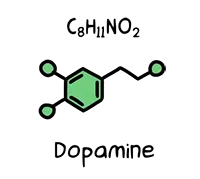

There are hundreds of types of neurotransmitters, but only a few appear relevant to the biology of depression. Let's look at three major suspects: norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin.

Antidepressants were discovered quite accidentally when a tuberculosis drug called isoniazid was found to have euphoric effects on patients. Soon, its sister drug was trialled on people with and without TB, many of whom showed increased vigour and appetite, weight gain, improved sleep, and greater sociability.

In the 1950s, two early classes of antidepressants were born:

- Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs) slow down the enzymes that break down norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin in the synaptic gap. The result: these neurotransmitters stick around in the synapse for longer, giving them more opportunities to signal the receiving neuron.

- Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs) also cause these neurotransmitters to stick around longer, but they do so by gumming-up the reuptake pumps that recycle them back into the transmitting neuron. Once again, the chemical message is sent more times.

Why do these drugs work as major depression treatments? And why are norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin the targets?

Norepinephrine

Norepinephrine (or noradrenaline) drives the fight-or-flight response, mobilising the body and brain for action under stress. As a neurotransmitter in the brain and spinal chord, it increases your alertness, arousal, and attention.

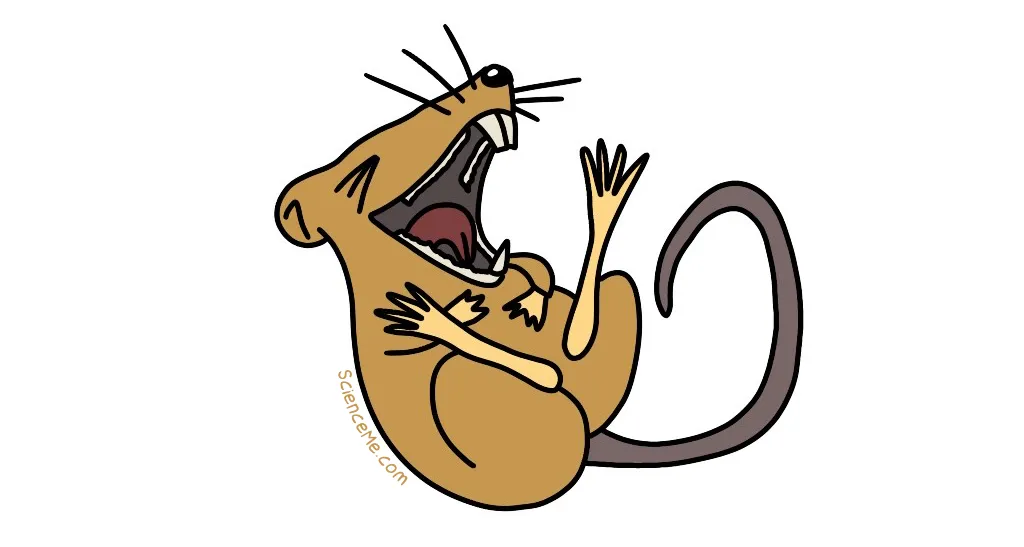

If you put an electrode in a rat's brain to stimulate the release of norepinephrine, it makes the rat unbelievably, ridiculously, insanely happy.

How do you know when a rat is happy? The trick is to make him work for something: train a rat to push a lever in exchange for a hit of norepinephrine and he'll push the lever all day. It's at least as good as food, sex, or drugs.

Humans are also highly motivated by norepinephrine. Here's a non-exhaustive list of things that stimulate norepinephrine release in humans:

- Having sex

- Scratching an itch

- Eating cookies in winter

- Playing in the leaves after dinner

These are all pleasurable, stimulating activities, so we might make the hypothesis that anhedonia (the inability to feel pleasure) is caused by a shortage of norepinephrine. There are just two problems with this idea.

If you throw a few MAOIs or tricyclic antidepressants into a person, it makes a difference to their norepinephrine levels within hours. However, their depression symptoms don't improve for weeks. Something's wrong with this picture.

"Wait!" You shout. "That's just one problem! You clearly stated there are two problems with the norepinephrine hypothesis! I am angry!"

Good point. The second problem is that while norepinephrine is involved in the pleasure pathway, it plays second fiddle to another powerful neurotransmitter: dopamine.

Dopamine

Dopamine is also released when we have sex, exercise, meditate, go shopping, pat a dog, watch a movie, and take cocaine. It's highly addictive stuff, so when we find an easy way to stimulate it, we end up repeating that behaviour a lot.

However, dopamine is more about the anticipation of pleasure than pleasure itself. It even helps us pursue long-term rewards, being produced at the mere thought of rewards that are uncertain or far into the future, like retirement plans or the afterlife.

As well as its role in this anticipation–reward system, dopamine also helps regulate our emotional responses, memory, and movement. Abnormal dopamine levels have been linked to various neurological conditions like Parkinson's, schizophrenia, and autism.

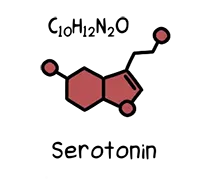

Serotonin

Serotonin helps us feel happy, balanced, and focused. It appears to be depleted by chronic pain and anxiety, as well as poor sleep and nutrition—all deleterious factors associated with depression.

By the 1980s, Prozac promised to become the new frontline treatment for depression and anxiety. It was the first of many selective reuptake inhibitors, which slow the recycling of neurotransmitters at the synaptic gap.

- Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) sustain serotonin levels in the brain and include citalopram, dapoxetine, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, sertraline, and vortioxetine.

- Serotonin and Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs) sustain both serotonin and norepinephrine in the brain and include venlafaxine, milnacipran, levomilnacipran, duloxetine, and desvenlafaxine.

The data so far strongly suggest a relationship between these three main neurotransmitters and the symptoms of depression. Simplistically, we might hypothesise that anhedonia is caused by low dopamine. Psychomotor retardation is caused by low norepinephrine. And guilt, grief, and obsessive thinking are caused by low serotonin. But you knew it was never going to be quite that simple.

Substance P

A latecomer has arrived at our party. Meet the neurotransmitter known as Substance P, expressed in the nervous system and in immune cells. Substance P causes pain and inflammation when the body is under attack, regardless of whether the threat is a virus or a particularly sharp Lego brick.

Drugs that reduce Substance P signalling can have a profound impact on people with major depressive disorder. They get better without any traditional antidepressant treatment whatsoever.

What the hell? The same neurotransmitter plays a role in both major depression and real physical pain. This just complicates things further, while reminding us that the biology of depression is complex and still not fully understood.

Neuroanatomy and Brain Surgery

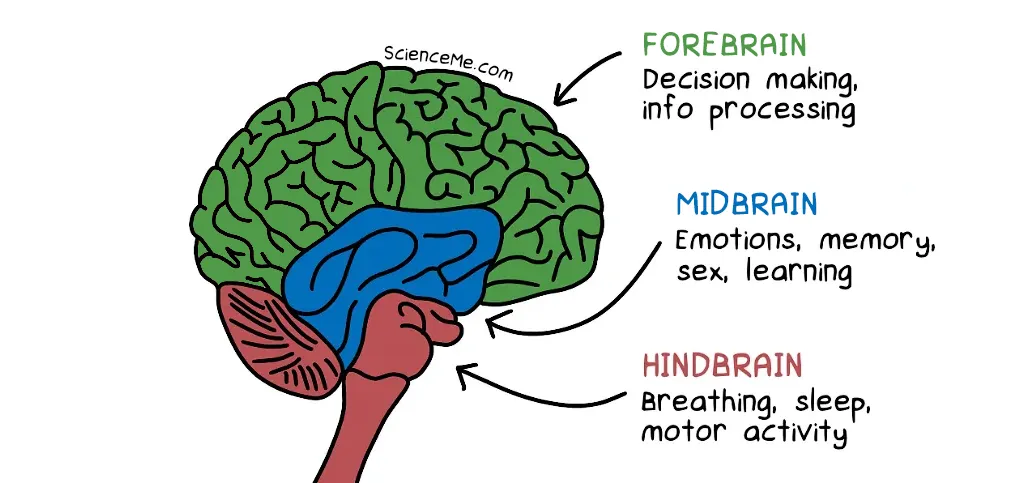

The triune brain theory is an evolutionary theory of brain development that emphasizes three key regions that function relatively independently in coping with stress via fight-or-flight, emotion, and cognition.

The hindbrain includes the brainstem and the cerebellum, and was the first part of the brain to evolve in animals. It does a lot of critical bodily functions on autopilot, regulating our breathing, blood pressure, homeostasis, and beyond.

The midbrain includes the limbic system and processes memories and emotions, while transmitting messages to the hindbrain. When an elk sees a rival elk, the limbic system creates fear and tells the hindbrain "prepare to fight or flee".

The forebrain includes the cerebral cortex and is where primates and especially humans were dealt a Royal Flush. Decision making, visual processing, abstract thinking, and problem solving are all handled by this modern brain extension.

Imagine you're a caveperson. You go for a walk in the forest, on the lookout for fruit or cheeseburgers or whatever cavepeople ate. Suddenly, a wild pig rushes you and gores you in the stomach. What happens in your brain?

At least three things. Psychomotor retardation helps you preserve energy and limit pain. Grief builds a negative association between wandering into wild pig territory and your new predicament. Anhedonia causes you to lose your appetite for food or sex, thereby limiting risk taking behaviour while you're wounded.

Major depressive disorder looks a lot like the brain having a chronic stress response. And it turns out you don't even need to be gored by a pig to set off the cascade.

If you sit and worry about the starving African children on the news, your brain reacts as if there are children starving in your own community, perhaps even your own kids, as if the problem is happening directly to you. Bear this in mind when you ruminate. While your cortex spins stories of stress and despair, your midbrain and hindbrain can't differentiate these thoughts from real experiences.

Surely there's a way we can break the link between stressful thoughts and our emotions?

Yes! This is a cingulotomy. It's an irreversible neurosurgical treatment for desperate people suffering from MDD, OCD, or chronic pain.

A singular bundle cut between the cortex and limbic system significantly reduces depression symptoms, in part by stopping the constant doom messaging from filtering down to the midbrain and hindbrain.

A cingulotomy is a radical procedure, reserved for those who have tried antidepressants, psychotherapy, and even electroconvulsive therapy to no avail. Amazingly, though, with a cingulotomy around 60-70% of people get better.

Separating your sad abstract thoughts from your emotions is one thing. But what about your happy abstract thoughts? The procedure can't selectively block the negative pathways alone. All thoughts and emotions become disconnected.

This is why a cingulotomy is a last-ditch resort, reserved for those whose every moment is defined by emotional anguish. But it's still a valuable option in our toolkit. If a man on fire cries out for help, you don't tell him that extinguishing the flames would deprive him of warmth. Being on fire gives no quality of life whatsoever.

Hormones and Women's Health

Thyroid Hormones

Thyroid hormones are a cluster of chemical messengers that control metabolism, growth, and various other bodily functions. If your thyroid acts up and fails to make enough of these hormones (a condition called hypothyroidism) lots of bad things happen which often includes a descent into depression. It's estimated that hypothyroidism accounts for 20% of all cases of Major Depressive Disorder, and the first line treatment is a hormone replacement drug called levothyroxine.

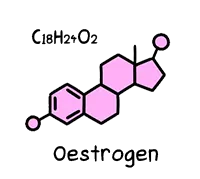

Oestrogen

Oestrogen is a steroid hormone which develops and maintains female characteristics. Known for our haphazard and blatant production of this hormone, women have twice the risk of developing depression than men. The high-risk times are when oestrogen levels fluctuate the most dramatically: just before a period; after giving birth; and during perimenopause.

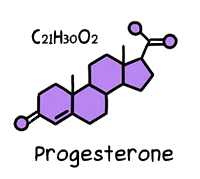

Progesterone

Progesterone is a sister molecule to oestrogen. Every month, it makes the lining of the uterus a safe, friendly space where a fertilised egg can grow. It also surges during pregnancy to trigger changes that nourish the foetus, suppress premature contractions, and prepare the body for breastfeeding.

Unstable progesterone levels are also correlated to major depressive disorder. Too much synthetic progesterone via birth control pills or implants, as well as too little natural production of progesterone due to perimenopause, can lead to dramatic mood swings.

What's difficult to untangle is the relative relationship between specific female hormone and depression. Evidence suggests that the ratio of oestrogen to progesterone is important. After giving birth, these hormones jump around like a rat on a tramp, having significant effects on the signalling of the major neurotransmitters we discussed earlier.

Regardless of what happens at the nuts and bolts level (neuroanatomy), additional factors like the rise and fall of hormones also have an effect at the neurochemical level.

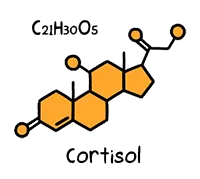

Cortisol

Sapolsky has dedicated the last 30 years of his life to studying a class of stress hormones called glucocorticoids, which are secreted by your adrenal gland in times of stress. The human version is called cortisol.

Cortisol is essential to your survival, increasing the glucose in your bloodstream and brain so you can level-up your performance in short bursts when needed. However, cortisol can become dysregulated, interfering with dopamine levels and creating other cascades of effects around the body. Cushing's Syndrome is the result of too much cortisol over a prolonged period of time, while Addison's disease is the severe lack of the stress hormone.

Half of all people with major depressive disorder show significantly elevated levels of cortisol. Why? Remember that at peak times, the brain of a depressed person is undergoing a massive stress response. There's a chronic battle going inside their heads, making them feel stressed, anxious, fearful, hyperalert, irritable, angry, scared, and other dreadful emotions.

Statistically, your first major depressive episode is likely to occur after a major life stressor. If you have insufficient coping strategies, you will be flooded with cortisol which leaves you at higher risk of developing depression.

If you recover from the depression, you're at no more at risk for developing depression in future than anyone else. If you bounce back from a second depression-inducing event, you're still safe. The problem occurs somewhere around the fourth or fifth major life stressor that sends you spiralling. At this point, the depression starts cycling as a generalised biological stress response all on its own, and you don't even need an external life stressor to trigger another episode.

The Psychology of Depression

We all feel the psychological effects of stress in our lives, and we take measures to cope with it as best we can. Unfortunately, life can throw some real whoppers our way, taking us to the pathological extreme of stress. Depression is near when:

- We have no outlets for stress-relief

- We lack control over our stressors

- We don't know when the stressor will return

- We lack the social support to cope

What happens if an abominable seagull flaps into your house each morning and pecks at your skull? Ideally, you shoo it away and get on with your breakfast. You may even shut the window so it can't happen again.

The major depressive will sit at the breakfast table morning after morning and accept their life now involves a daily skull-pecking. This is the cognitive distortion of major depression. We're unable to see past the bad situation that sucks the joy out of life. The lack of control leads to feelings of chronic helplessness.

If you lose a parent to death at age 10 or younger, for the rest of your life you're at greater risk of major depressive disorder.

This makes sense because for our first 10 years, we're learning about cause and effect. We learn to what degree we have any efficacy or control. If a primary attachment figure dies while we're still learning about the world, we cement the belief that traumatic things happen over which we have no control. This brings us closer to the cliff of learned helplessness for the rest of our lives.

Genes vs Environment

Major depression is a genetic disorder. The closer your relationship to someone with depression, the more likely you are to share the same depression-linked genes and develop it yourself.

| Relationship | Risk |

| Identical Twins | 50% |

| Siblings | 25% |

| Half-Siblings | 8% |

| Strangers | 2% |

The glass half-full chap will be quick to notice that even if you have a genetic predisposition to depression of 50%, you also have a 50% chance of not developing depression, all else being equal.

So while genes play a significant role in depression, it's no more than all the environmental factors combined.

The genetic causes of depression are not about inevitability, they are about vulnerability. Indeed, a gene linked to serotonin production was found to indirectly relate to depression. It doesn't matter if you inherit the vulnerable version of the gene or the protective version unless you have a history of major life stressors growing up.

Psychological stressors like parental divorce, abuse, or the death of a close family member, must occur before the effects of the gene kick in and raise your vulnerability to depression.

In a longitudinal study of New Zealanders over many years, people with the vulnerable form of the gene experienced major depression at a rate of 30x more than people with the protective gene.

Tying it all neatly into a little bow of despair, it turns out the aforementioned glucocorticoids regulate this gene. This links together our environment, our genes, our biology, and our psychology in the causes of depression.

Final Thoughts

What do we know about major depressive disorder today?

- Depression hinges on stress at the intersection of biological, environmental, and psychological factors.

- Depression risk is heightened when childhood trauma activates genes and creates psychological vulnerabilities.

- Depression is at least 50% biological in its origins.

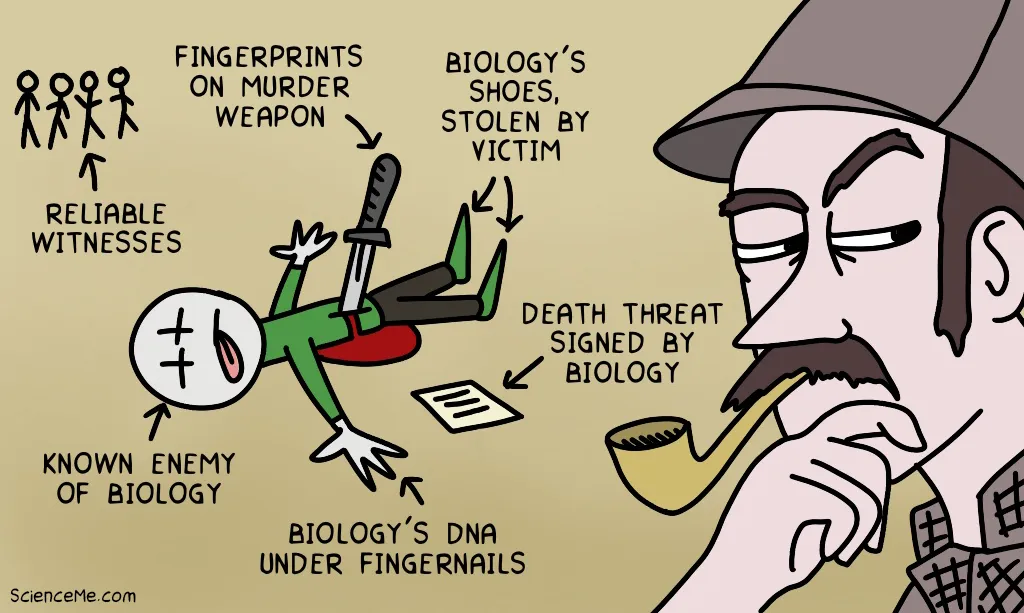

Who did the crime?

Depression is all around us, yet so is the stigmatised embarrassment we have with the idea of mental illness. Sapolsky says one of the greatest things a disease researcher can hope for is that a politician's loved one is struck down by it, because they'll start a foundation, get research funding, and bring us all closer to the cure.

This is not the case for mental illness. We're still too ashamed to talk about it. Anxiety and depression are still widely seen as weak and shameful states to be kept secret. Perhaps if we can start to recognise the biology of depression, we can feel less shameful. Because suppression is the worst thing we can do. To deny we are sick is to deny any chance of getting better.

Free Depression Helplines

- United States / 1-866-728-7983 (Feelin Kinda Blue)

- Canada / 1-833-456-4566 (Crisis Services)

- United Kingdom / 116 123 (Samaritans)

- Australia / 1300 22 4636 (Beyond Blue)

- New Zealand / 0800 111 757 (Mental Health Foundation)

- National Institute of Mental Health

Watch Dr Robert Sapolsky's full lecture on which this article was based:

Written and illustrated by Becky Casale. If you like this article, please share it with your friends. If you don't like it, why not torment your enemies by sharing it with them? While you're at it, subscribe to my email list and I'll send more science articles to your future self.