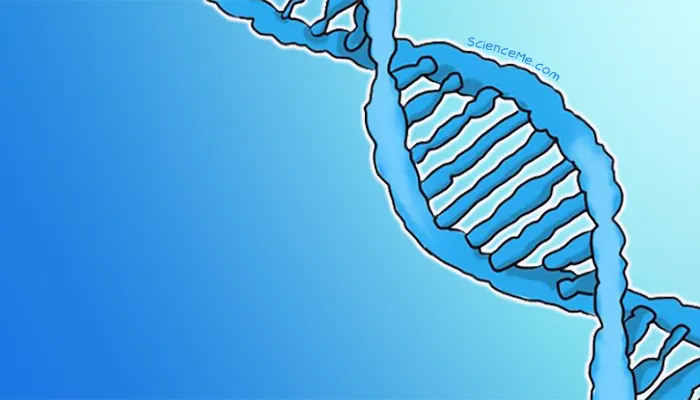

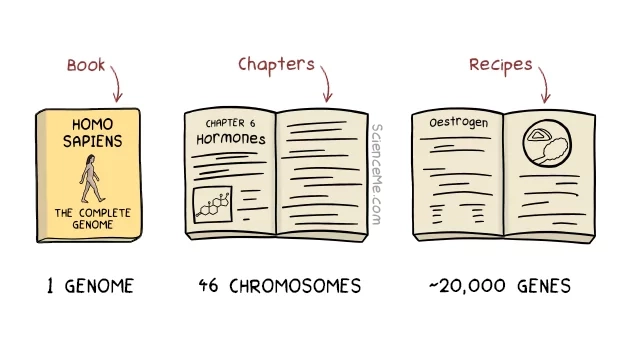

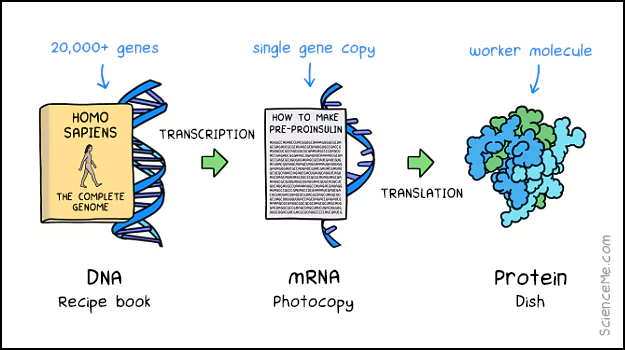

Think of your DNA as a recipe book. Chromosomes are the chapters. Genes are the recipes. Here's how we make the dish.

DNA, Genes, and Chromosomes: The Basics

Your complete DNA set, called your genome, contains over 20,000 genes. Each of your roughly 30 trillion body cells carries this entire genome—except red blood cells and cornified skin, hair, and nail cells.

The strings of data in DNA direct your cells to make the proteins that make up your body. If you think of your genome as a cookbook, then chromosomes are the chapters and genes are the recipes. Proteins made from these genes perform nearly every function in your body, from muscle contraction, to immune defence, to brain signalling.

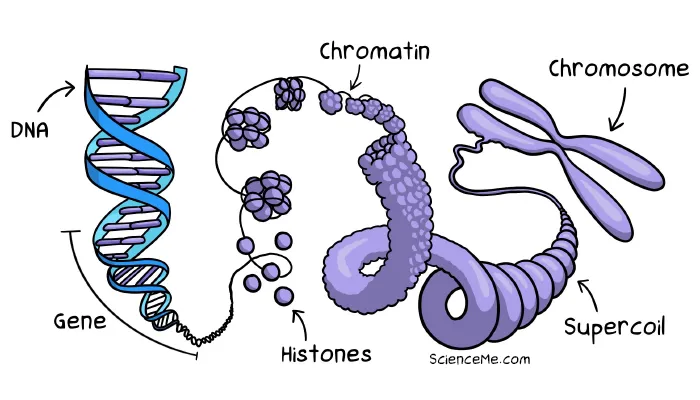

Most of the time, DNA exists in the nucleus as long, delicate strands called chromatin. Only when a cell prepares to divide does this chromatin condense into 46 tightly coiled chromosomes.

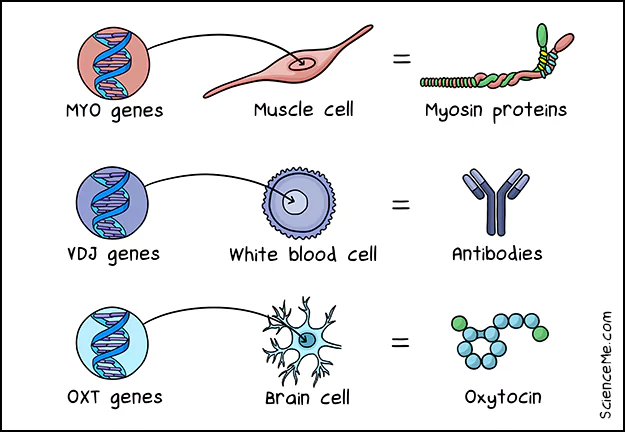

Genes are translated into strings of amino acids which then twist and fold into proteins. Proteins perform critical roles, from the myosin in your muscles, to the antibodies in your immune system, to the neurotransmitters in your brain.

The Structure of DNA

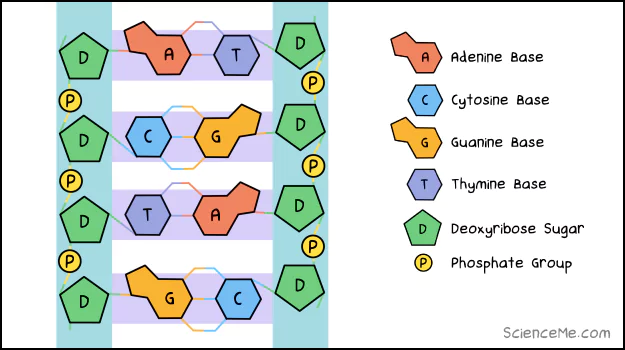

You likely know that DNA forms a famous double helix, with rungs made of complementary base pairs: adenine (A) pairs with thymine (T), and cytosine (C) pairs with guanine (G). The precise sequence of these bases encodes the recipes for proteins.

In The Mysterious World of The Human Genome, Frank Ryan offers the analogy of DNA as a train track stretching to the horizon, with each of the 3 billion base pairs acting as a sleeper. That's your genome.

How Does DNA Work?

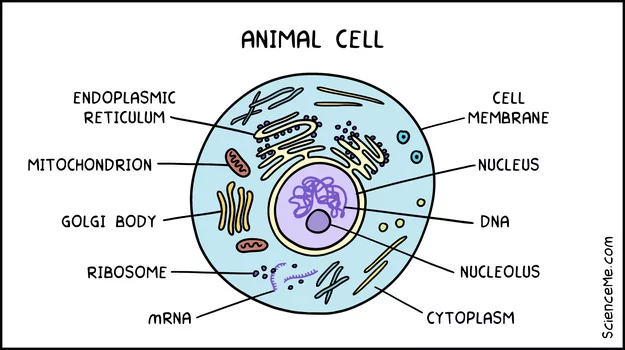

Now that we have an idea of the structure, how does DNA work? How does is it mechanically converted into proteins to keep us alive on a moment-to-moment basis? We need to zoom out to our cells: the multipurpose biological factories that make up our tissues.

Cells have complex internal structures bustling with organelles and proteins that keep us alive. They look like this without the labels:

Besides water and fat, your body is made almost entirely of proteins. These include enzymes that drive digestion, hormones that coordinate growth, and antibodies that neutralise invading pathogens.

DNA isn't only a blueprint for foetal growth. It's essential to your ongoing survival, like making insulin if you've just had breakfast or cortisol if a wasp lands on your eyeball.

The Central Dogma describes how our genetic recipes are copied on-demand into disposable carrier molecules and converted into protein products.

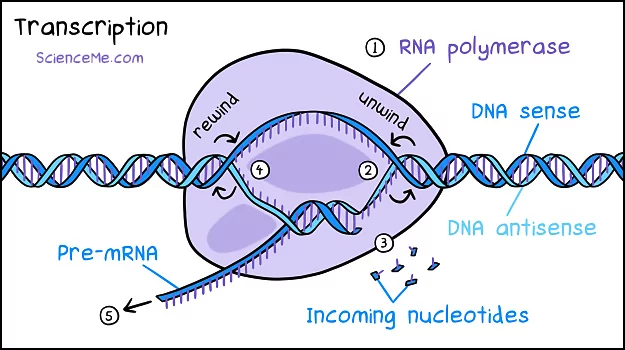

Step 1. Transcription (Gene Duplication)

So it's time to express a gene. A helper molecule known as RNA polymerase attaches to your DNA and teases apart the two strands of the double helix, unwinding the ladder as it travels along the gene.

This exposes the anti-sense strand, which contains complementary bases perfectly opposed to the sense strand.

With the anti-sense strand exposed, free-floating nucleotides attach themselves to their base partners to build a new sense strand. The emerging genetic string is called pre-messenger RNA (pre-mRNA).

Transcription Illustration. (1) Initiation. RNA polymerase binds to a promoter sequence at the start of a gene. (2) It unwinds the double helix to expose the anti-sense strand. (3) Elongation. A pre-mRNA transcript of the gene forms out of free-floating nucleotides. (4) RNA polymerase re-winds the original strands back into the double helix. (5) It cuts the pre-mRNA strand loose when it reaches a terminator sequence.

This beautiful molecular dance happens at astonishing speeds, all driven by spontaneous chemical interactions.

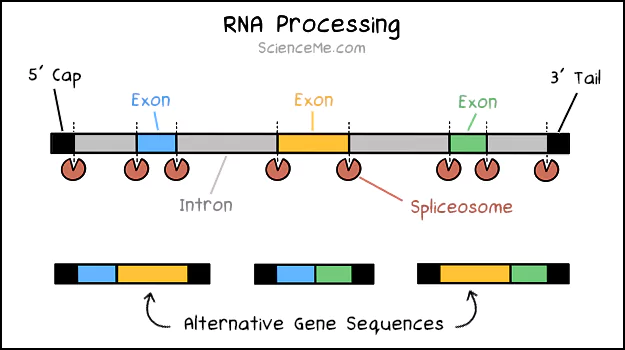

Step 2. RNA Processing (Gene Customisation)

Remarkably, your DNA recipe book is written in such a way that a single recipe can be cut and pasted into different elements to produce multiple alternative dishes. The biological term for this is alternative splicing.

So let's customise the dish. Spliceosomes sidle up to the pre-mRNA strand to make edits. They snip out non-coding sequences of bases called introns, leaving behind selected coding sequences called exons. (Memory hack: exons go on to exit the nucleus.)

On average, there are 9 exons per gene. The freakishly long dystrophin gene has 79 exons spanning 2.3 million bases.

RNA Processing Illustration. Spliceosomes remove non-coding introns from the pre-mRNA strand, leaving only the desired exons to customise the gene recipe.

Step 3. Translation (Protein Production)

So far, we've copied and edited the recipe. Now let's actually make the dish.

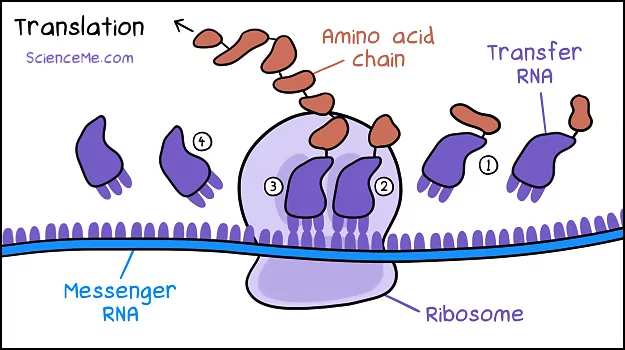

The finished mRNA strand exits the nucleus and lands in the fluid cell cytoplasm. Ribosomes then bind to the mRNA strand and read the bases in groups of three, called codons. Each three-base codon is matched to complementary anticodons on free-floating units of transfer RNA.

Each transfer RNA carries a specific amino acid. Thus, spontaneous chemical bonding sees the mRNA strand translated into a reproducible sequence of amino acids.

Translation Illustration. (1) Free-floating tRNAs approach the ribosome carrying specific amino acids. (2) Spontaneous reactions cause mRNA codons to temporarily pair with complementary tRNA anti-codons. (3) The ribosome builds a chain of amino acids. (4) The spent tRNA is cut free. The amino acid chain is released when the ribosome reaches a stop codon.

The amino acid chain is now known as a peptide. What starts out as a linear string rapidly twists and folds into a 3D structure thanks to atomic bonds and hydrophilic and hydrophobic interactions. And they go on to connect with each other to form polypeptide complexes... also known as proteins.

After a little more molecular tweaking, the final protein products are packaged off to fulfil their destiny outside the cell (eg, signalling hormones) or are retained inside the cell as molecular worker (eg, more ribosomes). Voila.

The Genetic Code

"Tell me more about the codons!" I hear you scream. And you'd be right. This is a good thing to scream about if anything is.

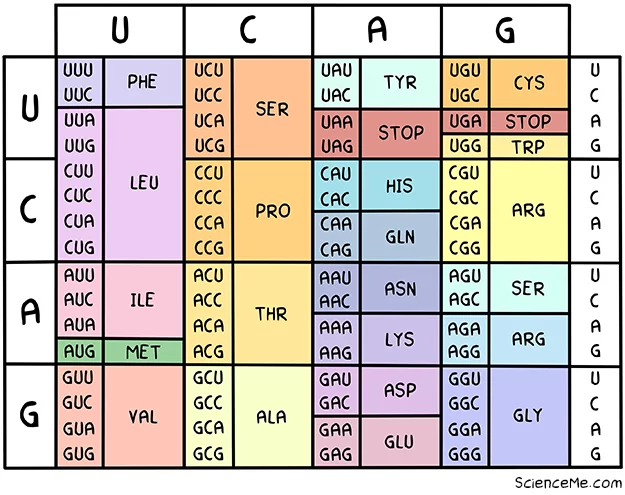

The RNA alphabet has only four letters (A, U, C, and G). Since codons occur in groups of three, it means there are only 64 words (4 x 4 x 4) in our codon dictionary.

As it happens, that's more than enough. Because the human body only uses 20 amino acids. The rest of the codons just double up, or act as start and stop signals for the ribosomes. Since every gene begins with a start codon (AUG), all peptides also start with methionine. Typically, 2-50 amino acids follow in sequence because the stop codon signals the end of the chain.

The Codon Table: The genetic code reveals how 64 codons refer to just 20 amino acids.

| Ala = Alanine | Leu = Leucine |

| Arg = Arginine | Lys = Lysine |

| Asn = Asparagine | Met = Methionine |

| Asp = Aspartic Acid | Phe = Phenylalanine |

| Cys = Cysteine | Pro = Proline |

| Gln = Glutamine | Ser = Serine |

| Glu = Glutamic Acid | Thr = Threonine |

| Gly = Glycine | Trp = Tryptophane |

| His = Histidine | Tyr = Tyrosine |

| Ile = Isoleucine | Val = Valine |

How Fast Does DNA Work?

Depending on the size of the gene, it takes between 20 seconds and several minutes to produce a single protein molecule from mRNA.

Multiple ribosomes work along the same mRNA strand, with just as little as 80 nucleotides separating them, in order to produce multiple peptide chains simultaneously. And there are up to 10 million ribosomes building on demand in every cell.

It's all rather amazing, really. Your DNA and its entourage perform a constant choreography, culminating in the normal functioning of any living organism, such as a friendly old toad. Isn't that brilliant?

How Does DNA Mutate?

Now you know how DNA works—but what happens when things go wrong?

Every time a cell divides, it must duplicate its entire genome of six billion bases for the daughter cell to carry forward. While the base pairing of DNA is extremely reliable, there are still plenty of opportunities for error, estimated at a rate of 1 in 100 million bases per generation in humans.

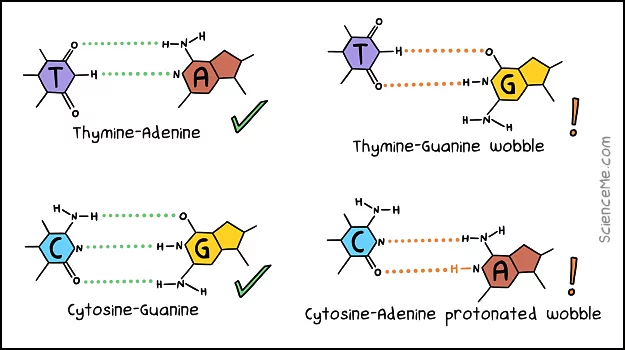

In mispairings, bases form hydrogen bonds between the wrong atoms or gain an extra proton to create a "protonated wobble".

Any addition, substitution, or deletion of an A, C, G or T base is considered a mutation, with the potential to change an entire gene recipe and its protein product.

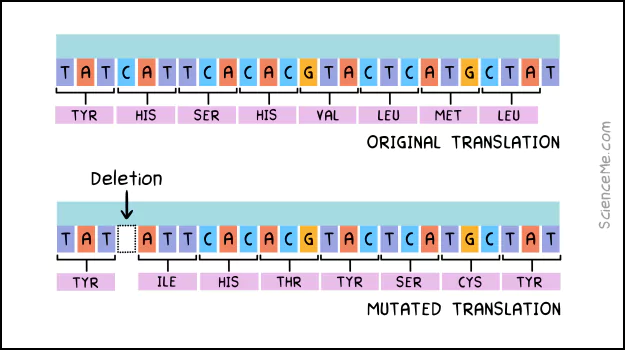

Here's one example. In a frameshift mutation, a single base is deleted from the master DNA strand. It shifts the codon reading frame, so all the subsequent bases are displaced. When the gene sequence is translated, it produces a different string of amino acids.

A frameshift mutation caused by a single base deletion can corrupt the entire protein product.

Of course, DNA mutation isn't always bad. When it occurs in sperm or egg cells, or during early embryonic development, it can be the initiating factor for evolution by natural selection. The problem is that mutation is a blind trial-and-error process. Sometimes it gives you a kick-ass adaptation, sometimes it makes no difference whatsoever, and sometimes it creates disease.

Genetic mutations are known to cause more than 6,000 diseases in humans, from those present since birth to those that develop over the lifetime. Find out how we're learning to permanently fix these errors in my article How Does Gene Therapy Work?